9 Development & Changes in Digestion & Sleep

Development & Changes in Digestion & Sleep

“Eat, Sleep, Be Happy, Repeat”

-Anonymous

Eating and Digestion

We all need nutrients and water to survive, otherwise our organ systems would not have the support

and energy they need to function. Without the nutrients we get from food and water, we cannot develop, grow and mature, and our systems will have difficulty making adjustment and repairs as needed. Ingestion, which is the taking in of food, liquids, and other substances, and elimination, which refers to getting rid of waste the body doesn’t need are critical for maintaining everyday and long-term functioning of the body and mind.

Digestion begins with ingestion or eating, which may seem simple, yet is quite a complex process. It is a motor activity that requires neuromuscular coordination for mastication (chewing) and deglutition (swallowing) as well coordination with the respiratory system so that breathing and eating can occur at the same time. The body structures involved in ingestion are the mouth, teeth, tongue, and esophagus. Once food gets into the mouth, saliva initiates a chemical breakdown of the food and the tongue moves it around as chewing occurs. Just before swallowing, the tongue pushes a bolus of food to the back of the throat and into the esophagus.

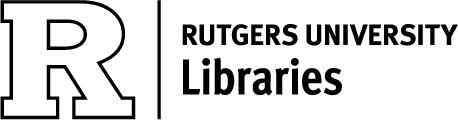

Figure 9.1 Digestive System

After ingestion, the processes of digestion and absorption begin. Food moves from the esophagus to the stomach. Along the way, the epiglottis receives a signal to cover the trachea so that food and liquids do not end up in the lungs. The stomach continues to break down the boluses of food through muscle action and the release of gastric acids.

The next step along the digestive tract is the small intestines where food is broken down further with the assistance of chemicals that are manufactured or stored in the pancreas, liver and gallbladder. The work of the small intestine facilitates absorption of important vitamins, minerals, proteins, carbohydrates, and fats. Then, blood that is rich in nutrients goes to the liver, which filters out waste and works as a storage container for some vitamins and glycogen, a form glucose that provides energy when released.

After nutrients are removed from food, left over waste material passes through part of the large intestine called the colon. Here is the last chance for the body to absorb water and minerals. As the water absorbed, the waste is prepared for elimination by moving through the large intestine. Along the way it becomes more solid and gets pushed into the last stop along the digestive tract known as the rectum. Waste, now known as feces, leaves the body through the anus.

Prenatal

The digestive system can also be referred to as the gastrointestinal tract or “gut”. Prenatally, the gut begins developing at approximately four weeks of gestational age. Over the next 4 – 18 weeks, peptides, proteins, and hormones begin to circulate, which facilitate development and functioning of the digestive system (Aynsley-Green, 1985) even though the fetus primarily uses glucose for growth and development, which is primarily obtained from the mother’s blood. Between five to seven months of gestational age, the gastrointestinal tract approaches that of a neonate with peristaltic movements and a liver that can secrete bile. Meconium, a dark, gooey substance of unabsorbed amniotic fluid and waste is continuously formed and is excreted as the newborn’s first “poop”.

Infancy and Childhood

After birth, infants must regulate their own blood levels of glucose, fat and proteins through the ingestion of food and liquids. Fortunately, the primitive reflexes that allow infants to eat such as “rooting” and “suck-swallow” developed while they were in the womb. Human milk is the best source of nutrition because it includes not only calcium which is important for development, it also immunoglobulins that reduce the risk of infection and proteins that facilitate development of a healthy gastrointestinal tract with beneficial gut bacteria (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2012).

During infancy, food ingestion changes from a reflexive “suck-swallow” activity to a voluntary activity, between two – five months of age. Voluntary sucking includes modifying the shape of the mouth and prepares the tongue and mouth for speech. At approximately six months, infants are ready to begin transitioning to solid, yet soft food because they are able to maintain an upright sitting posture for short periods of time, the gastrointestinal tract is maturing which accounts for more digestive enzymes, and the kidneys are able to handle the higher osmolar load of solid foods. These are all timely developments because after six-months of age, infants will not be able to obtain sufficient nutrition from milk alone.

Figure 9.2 Infant Eating

Chewing behavior begins between five – eight months, which is consistent with the eruption of teeth, and the need for solid food. Oral control continues to improve such that infants are able to close their lips around a spoon and can learn to drink from a cup.

Adolescence

The gastrointestinal system matures quickly from ten to 20 years of age including the appearance of all 32 teeth. Stomach capacity and gastric acidity increase during adolescence, which correlate with an increase in appetite. Muscles of the stomach and intestinal walls become thicker and stronger and the liver reaches its full size and function. The fluid and

electrolyte changes that occur during adolescence reflects changes in the musculoskeletal system and body composition (Murray & Zentner, 2001).

Adults and Older Adults

Generally speaking, adulthood is a time when the digestive organs are optimally functioning. However, many changes occur in older adulthood which can interfere with eating, digestion and absorption. In the mouth, saliva flow decreases, the oral mucosa atrophies and dental decay and progressive gum recession can lead to loss of teeth. All of which can interfere with chewing and the initial stages of digestion. Aging changes in the gastrointestinal tract also include a reduction of digestive enzymes, slowed peristalsis, and reduced hepatic synthesis.

Together, these changes can have a negative effect on nutritional absorption, thereby leaving older adults with nutritional deficits even if their intake appears to be adequate. Impaired gastrointestinal absorption may also play a role in the effect medications have or don’t have on older adults. Beyond absorption, changes in muscle tone and digestive enzymes can lead to difficulties with elimination, including constipation and fecal impaction. (Murray & Zentner, 2001). To address these negative effects of aging, older adults can improve gastrointestinal

functioning by consuming high fiber foods, achieving adequate hydration and participating in regular physical activity.

More About Elimination

Defecation is the term used to indicate the elimination of fecal material, whereas micturition is the act of eliminating urine. The urinary system is comprised of two kidneys, two ureters, a bladder, and a urethra and is responsible for the management of liquid waste. Normal function depends on communication between the nervous, endocrine and vascular systems. Maturation of the urinary system occurs throughout infancy and into childhood. Initially, the bladder with respond to a small amount of urine by contracting and eliminating it. Toddlers around two years of age will begin to develop a sense of awareness of needing to void, however they need to have adequate strength of the diaphragm, abdominal, and perineal muscles in order to be able to control urination. Mature bladder control is typically achieved between three – five years of age (Murray & Zentner, 2001).

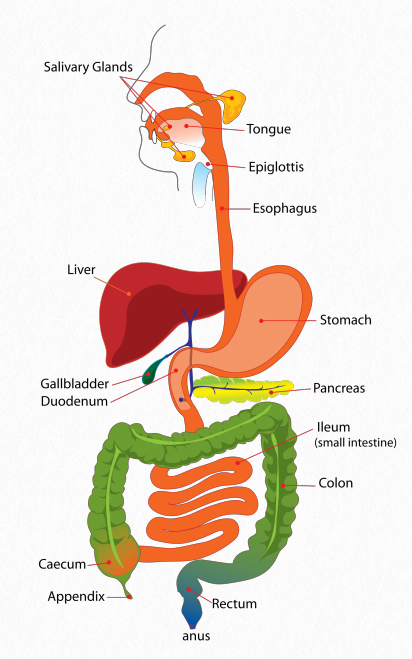

Figure 9.3 Urinary System

Similar to the gastrointestinal system, functioning of the urinary system is unremarkable during adulthood. However, during older adulthood, there is impaired functioning of the kidneys and bladder. The kidney decreases in size and suffers a loss of nephrons, which is the functional unit of the kidney. The bladder also loses capacity in older adulthood due to declines in muscle strength, elasticity and size. This can put older adults at risk for urinary incontinence (UI), which is an involuntary loss of urine. Although not inevitable, the incidence of UI is

higher in older adults than in younger adults.

Sleep

When it comes to physical and mental functioning sleep is probably just as important as food. It allows time for the body and the mind to rest, which helps with attention, concentration and clarity of thought. Sleep has also been associated with consolidation of thought and memories (Rasch & Born, 2013). Physically, sleep assists with the maintenance of

homeostasis helping to combat type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease, and our ability to respond to threats including viruses.

Humans have an internal “body clock” that operates on a 24-hour cycle known as the circadian rhythm. The sleep-wakefulness cycle consists of periods of sleep lasting from six to ten hours, and periods of wakefulness lasting from 14 to 18 hours a day. Light can influence the circadian rhythm, signaling the brain through the hypothalamus whether it is day or

night. The substances adenosine and melatonin also influential in the sleep-wakefulness cycle. Adenosine levels increase throughout the day as tiredness sets in and then breaks down during sleep. As natural light diminishes in the evening, melatonin, which induces drowsiness, is released.

Sleep occurs in four stages and be divided into two sleep states. The first three stages are collectively known as non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. The fourth stage is rapid eye movement (REM sleep). All these stages repeat cyclically throughout the night, with most cycles lasting between 90-120 minutes and NREM constituting approximately 75% of each cycle.

Here are the highlights of sleep’s stages. Stage 1 (NREM) is the transition from wakefulness to sleep when the heart rate, breathing and brain waves slow down, and muscles relax. During Stage 2 (NREM), heart rate and breathing continue to slow, eye movements stop, and the body temperature drops. Stage 3 (NREM) is when the muscles are at maximum relaxation and brain wave activity is at its lowest level. Stage 4 (REM) typically occurs 90 minutes after falling asleep and is the time when the eyes quickly move back and forth and the heart and

breathing rates begin to increase. Dreaming often occurs during this stage, and fortunately, because the arms and legs are so relaxed acting out dreams is nearly impossible. REM sleep also the time when recent experiences become consolidated into long term memories.

Prenatal and Infancy

Prenatally, fetuses have been observed to have alternating period of sleep and wakefulness at about 29 weeks of gestation. It is thought that sleep induces early development of central sensory processing centers. Newborns spend as much as 14-17 hours sleeping per day, with a four-hour sleep-wake cycle that appears to be related to gastrointestinal physiology. Nearly half their sleep time is spent in REM sleep which supports nervous system organization. A stable circadian rhythm is established between two – four months after birth and by four months the infant is sleeping a couple of hours less per day with 40% spent in REM sleep.

Figure 9.4 Infant Sleeping on His Back

Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (SIDS) is a sudden unexpected death of an infant less than a year old while sleeping and cannot be explained even through autopsy (Krause, et al, 2004). In 1994 the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) introduced the “Back to Sleep” program, which recommends that infants sleep on their backs. Since that time a “Safe to Sleep” campaign backed by the US National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) has continued to advocate that infants sleep on their backs. In the United States, putting infants to sleep on their backs has contributed to a 70% reduction in SIDS (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021).

Childhood

By age three, children are in REM sleep approximately 20%-25% of their total sleep time, which is the same for adults. Recommendations for the amount of sleep preschoolers should get is 10 – 13 hours, with many children taking a nap during the day. Recommendations from the Sleep Foundation is for children ages 6 – 13 to sleep 9 – 11 hours per day.

Adolescence

Along with the biological and psychological changes that occur during adolescent, so is sleep. Research has demonstrated that the regulatory processes of circadian rhythm and the sleep-wakeful ness mechanism changes during adolescence, making it easier to resist sleep in the evening. Nevertheless, the need for sleep does not decline, meaning that waking up early in the morning for class become very challenging (Carskadon & Barker, 2020). Often the educational demands during adolescence can lead to sleep deprivation, which is

becoming a mental health concern. Students who reported sleep duration of less than six-hours per day were found to be three times more likely to report risky-behaviors or suicide ideation compared to those who sleep eight hours or more (Weaver, et al, 2018).

Adulthood and Older Adults

Aging is associated with disruption of the sleep wakefulness cycle with approximately 50% of older adults having complaints about not being able to fall or stay asleep. Indeed, changes in slow wave sleep (Crowley, 2011) and alterations in hormone levels levels (Czeisler, et al, 1992) along with psychosocial factors and co-morbid conditions appear to contribute to fragmented sleep and interferes with achieving the recommended seven – eight hours of sleep per night. During the aging process, the length of time spent in sleep stages three and

four decreases with a decrease in the relative proportion of REM to NREM sleep. Older adults also transition from sleep to wake more quickly than younger people. This results in decreased sleep efficiency, leaving many older adults complaining that they can’t get a “good night sleep” (Crowley, 2011).

Tips for a good night sleep include 1) going to bed and getting up the same time everyday, 2) ensuring the bedroom is dark, comfortable and a little bit cool in temperature, 3) avoiding large meals, caffeine and alcohol several hours before bedtime, and 4) being physically active during the day (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2016).

Final Thoughts

Eating and drinking, digestion and sleep are essential activities for life and undergo remarkable changes from the time an infant is born to early adulthood. During adulthood functioning of the gastrointestinal and urinary systems remain relatively stable. However, declines in gastric enzyme and saliva availability, muscular strengthen, connective tissue elasticity, and circulating hormone levels challenge digestion and sleep in older adults. Strategies to promote good nutrition and sleep habits throughout the lifespan are important to support physical and mental well-being.

References

American Academy of Pediatrics. (2012). Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics, 129(3), e827–e841.

Aynsley-Green, A. (1985). Metabolic and endocrine interrelations in the human fetus and neonate. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 41, 399-417.

Carskadon, M. A., & Barker, D. H. (2020). Editorial Perspective: Adolescents’ fragile sleep-shining light on a time of risk to mental health. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 61(10), 1058–1060. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/jcpp.13275

Crowley, K. (2011). Sleep and Sleep Disorders in Older Adults. Neuropsychological Review, 21, 41–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-010-9154-6

Czeisler, C. A., Dumont, M., Duffy, J. F., Steinberg, J. D., Richardson, G. S., Brown, E. N., et al. (1992). Association of sleep-wake habits in older people with changes in output of circadian pacemaker. Lancet, 340, 933–936.

Krous, H.F., Beckwith, J.B., Byard, R.W., Rognum, T.O., Bajanowski, T., Corey, T., Cutz, E., Hanzlick, R., Keens, T.G., Mitchell, E.A. (2004). Sudden infant death syndrome and unclassified sudden infant deaths: a definitional and diagnostic approach. Pediatrics 114(1),234-8.

Murray, R.B., & Zentner, J.P. Health Promotion Strategies Through the Lifespan, Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2001.

Rasch, B., & Born, J. (2013). About sleep’s role in memory. Physiological reviews, 93(2), 681–766. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00032.2012

Sudden Unexpected Infant Death and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome (2021). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/sids/data.htm

Tips for Better Sleep (2016). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/sleep_hygiene.html

Weaver, M.D., Barger, L.K., Malone, S.K., Anderson, L.S., & Klerman, E.B. (2018). Dose-dependent associations between sleep duration and unsafe behaviors among us high school

students. Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics, 172, 1187–1189.

Images

Title page. Photo by Polina Tankilevitch from Pexels. Retrieved from https://www.pexels.com/photo/woman-inwhite-robe-eating-on-the-bed-6429547/

Figure 9.1 Digestive System. Author: Leysi24, CC BY-SA 3. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Digestive-system-for-kids.png

Figure 9.2 Infant Eating. Photo by Andrea Piacquadio from Pexels. Retrieved from https://www.pexels.com/photo/photo-of-woman-feeding-her-child-3820131/

Figure 9.3 Urinary System. Photo by Arcadian, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. Retrieved from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Illu_urinary_system.jpg

Figure 9.4 Sleeping Baby. Photo by Sui Viswanath from Pexels. Retrieved from https://www.pexels.com/photo/grayscale-photo-of-baby-lying-on-hammock-3909834/