11 Adaptive Management

The second topic in the holistic techniques group is adaptive management. Adaptive management is a systematic approach based on the idea of improving management by learning from outcomes. This technique includes iterative adjustments in plans over time based on knowledge gained during the process. In this chapter, we cover details of the process of adaptive management, its benefits and limitations, and end with a case study of the Glen Canyon dam adaptive management program.

BACKGROUND ON ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT

Adaptive management is a technique that befits important situations where information is inadequate or incomplete for use in making confident decisions. Adaptive management is best used for recurrent decision-making in which uncertainty about the decision is reduced over time through comparison of outcomes predicted by competing models against observed values of those outcomes (Moore et al. 2011). The strategy includes interdisciplinary teamwork to develop management options, models, hypotheses, monitoring, periodic assessment of management outcomes, and adjustment in management plans. The process is ongoing because it relies on repetition of the process to learn from management performance in a cyclic manner. The prominent benefits of adaptive management practices are integration of efforts and expertise of managers and scientists who learn from management performance.

Learning from management has a basis in science and is not meant to partition the roles of science and decision-making. Information generated by this process is seen as a benefit to both management and science, and the new knowledge can be applied in an orderly way to advance management effectiveness. With each iteration of the process, the adaptive management team explores alternative ways to achieve objectives, makes predictions of the intended outcomes, monitors successes or failures, and then reconsiders objectives and plans.

Adaptive management was introduced to the environmental field in 1978 with a book produced by C. S. Holling. He stated the original definition of adaptive management as “an integrated, multidisciplinary and systematic approach to improving management and accommodating change by learning from the outcomes of management policies and practices.” While this concept had been known since 1978, agency and ecological conservation programs have only recently begun to adopt this process (McFadden et al. 2011). Some notable cases drove this transition because of their progress (e.g., the mitigation of impacts in the Grand Canyon, waterfowl management across the continent, managing forests across eastern Canada, and restructuring water flows across the Everglades ecosystem). The scientific community played a direct role in these applications, and many scientists were involved in the adaptive management teams. Also, scientists are increasingly promoting the adaptive management process because it has a sound scientific basis and yields benefits for developing research (Haney and Power 1996). In recent years, adaptive management has been growing in the scholarly published literature (McFadden et al. 2011). The core ideas of learning, teamwork, and dealing with uncertainty are appealing to both scientists and practitioners (Johnson 1999; Medema et al. 2008; Smith 2011). The promise of adaptive management is substantial for complex ecological conservation problems, but the track record of its application is mixed (McLain and Lee 1996). This may be due to inconsistencies in use of the concept (Allen et al. 2011). It also maybe be due to the challenges of changing our society into one that values reflection and rewards thinking, sharing, humility and understanding.

THE ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT PROCESS

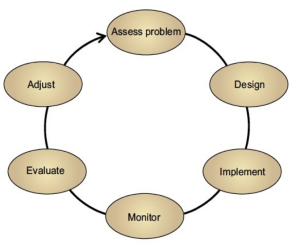

Often adaptive management is called learning by doing (Walters and Holling 1990), or sometimes trial and error management. The U. S. Department of Interior Technical Guide for adaptive management (Williams et al. 2009) defines the process as a systematic approach to improving environmental management by learning from outcomes. The adaptive management process in Williams et al. (2009) is illustrated as a six-step iterative process (Figure 11.1) that includes exploring management alternatives (assess problem), predicting outcomes from current information (design), selecting one or more alternatives (implement), measuring outcomes (monitor), determining success or failure (evaluate), and updating management actions (adjust). This is the general format of adaptive management.

The six-step process is consistent with the spirit of adaptive management and includes the learning from outcomes basis, but lacks emphasis on experimentation, hypotheses, and modeling to predict outcomes. Some organizations have created expanded adaptive management processes (Figure 11.2) which include more emphasis on tasks such as modeling (Delta Stewardship Council 2019).

UNDERLYING THEME OF EXPERIMENTATION FOR INTERDISCIPLINARY MANAGEMENT BY RESEARCHERS AND MANAGERS

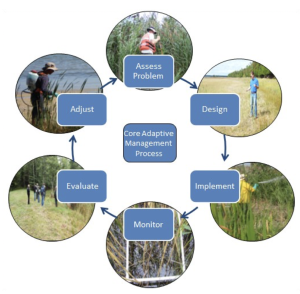

Management of the environment must deal with the ever changing nature of environmental systems and with the uncertainty that poses (Kato and Ahrn 2008). The dynamic nature of the environment puts managers and scientists under the same challenges because each wants to know what to expect from management policies. Thus came the idea that management can be treated as an experiment. Like any experiment, adaptive management is bounded in time, requires data collection, and has a stage where findings are used to evaluate hypotheses. Adaptive management tends to be adopted as agencies and managers shift to ecosystem-scale challenges like the response of fauna and flora to water management, climate change, and landscape change (Woods 2021) or management of phragmites in the Great Lakes (Figure 11.3) (Great Lakes Phragmites Collaborative 2016).

Research and management do not naturally go together. Under adaptive management, they are integrated because management actions are treated as experiments. Scientists do not specify the experiment, but they do work with the practitioners. As a team they design management options, then develop predicted outcomes, and identify measures of success or failure. Then scientists and managers work together to readjust management actions, building on the understanding they have obtained.

The interdisciplinary focus of adaptive management was a new concept when it was introduced (Dreiss et al. 2017). Managing complex environments on a large scale requires broad thinking from a team that has mixed perspectives and is willing to raise imaginative options. Adaptive management is best used when choices are difficult or uncertain for decision-making (Kato and Ahern 2008). The traditional thinking that a one-time assessment study can resolve what to do does not fit these situations (Walters 1986). Beyond a set of policy options, creative work has to be done on objectives, models, and designing a course of action as an experiment. Teamwork is needed to craft a policy direction and develop the expected outcomes and measures which can then be used to test predictions. Adaptive management is a big switch from a process where administrators select management directions based on their experience, to a team-developed strategy with explicit tradeoffs and predicted outcomes.

MODELING IN ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT

The repeating process in adaptive management involves: modeling, hypothesis testing, monitoring, and a set schedule for reevaluation. Modeling is fundamental to adaptive management, but the use of mod- eling is not to identify an optimal solution. The pursuit of a single, best solution to meet management objectives is not the goal of adaptive management. Instead, simulation modeling is aimed at predicting outcomes from a set of viable management plans. Often in adaptive management cases, there are substantial uncertainties and a weak understanding of the key drivers. Incomplete or erroneous models can provide false predictions, and that is part of this process. Predictions that prove inaccurate are a clear signal to change management direction, and they can provide lessons on the need for management change. Finally, the process of modeling also reveals data gaps, lack of understanding, and uncertainties. This is an important part of the process as these issues help to identify what knowledge may still be needed and provide learning experiences.

Modeling is used for predicting management outcomes and for developing options for action. Team- developed models integrate perspectives, expertise, and new ways of considering management alternatives, and they generate expected outcomes, hypotheses to be tested, and specific measures for testing. Model results are used to craft new hypotheses and design monitoring protocols that will yield data indicating whether a management strategy produced the expected outcomes. This comprises a step in the creative process of adaptive management. There is some risk that multiple models will be debated, which can stall progress in the adaptive management process. The prediction-test-readjust progression is iterative so the best policy choice is not necessary at the start of the adaptive management process. At the start, a management direction that has a reasonable chance of succeeding can be tested and possibly be replaced by a new management strategy. This raises one issue for the team: in the public policy arena, are risky decisions possible or desirable? Failed management strategies may provide valuable information and better management outcomes in time, but parties outside the process could blame agencies for taking too many risks and causing failure. Managers avoid this very strongly. However, if modeling indicates potentially successful options and reasons why their application can work, then the adaptive process is working and builds support for these choices.

The use of models in a team context suggests that simulation models need to be simple in structure and operation. This simplification allows a diversity of participants to understand model structure, key variables, and how predictions were made. Also, key drivers often shape outcomes whose details often do not matter in the larger context of complex ecosystem-scale management cases. Models for creative uses in defining a management plan and conveying the key drivers to the stakeholders and the public should be easily understandable. The point of modeling in adaptive management is not to produce accurate and precise predictions of outcomes. Instead, models are used to focus deliberations on options, hypotheses, and design measurements and monitoring for validating or refuting management outcomes. Over time, with numerous iterations of adaptive management, models should become more accurate, precise, and supportive of management directions.

HYPOTHESIS TESTING IN ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT

Learning under adaptive management comes from experimentation with management plans. Hypotheses are crucial for experimentation, so there is a need to be specific about them. Also, hypotheses should define monitoring specifics and be feasible for testing. Management choices are the basis for experimental opportunities. Traditional experimentation is reductionist, testing very narrow hypotheses to gain an understanding of specific mechanisms and questions. Under adaptive management, hypotheses are treated holistically and aimed to perform objectively. Thus hypotheses should be focused at the systems level and integrate a wide variety of system properties. Once a management plan is developed and the objectives defined, then management actions and monitoring should commence with the aim of detecting compliance with objectives. With the natural dynamics of environmental systems, it is important to define monitoring measures and schedules to detect the effects of management separately from the natural dynamics of the system.

MONITORING IN ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT

In management programs, monitoring is often seen as open ended with ongoing costs, and thus managers tend to avoid this activity. However, monitoring is of central importance in adaptive management because of the orientation toward treating management practices as experiments. Monitoring environmental properties serves three purposes under adaptive management. First, monitoring has to be aimed at collecting data to test the predictions of management outcomes. This is critical to iterations of adaption in management. Second, monitoring builds knowledge of responses by the environmental system. This is important to the learning process and is one of the benefits of the adaptive management strategy. Third, over time, monitoring builds a database of the performance of alternative management policies and actions. Monitoring should not be broad and aimed at measuring everything. Instead it should target management outcomes from model predictions, and be very specific to measures that can be used to test predictions. Over time, such monitoring will evolve with adjustments in management policies and plans. Because management effects can take years to materialize, monitoring requires careful planning and institutional arrangement to maintain the program for some time. Overall, monitoring has to be efficient and effective for testing predictions of management outcomes.

EVALUATING PERFORMANCE IN ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT

The adaptive term in the adaptive management technique indicates that management changes have to be considered. Once a management plan has been adopted with predicted outcomes and test data collected, it is time to evaluate management performance. The timeline should be set at the beginning of the process so that the experiment is defined and a schedule set to reevaluate management. Then the team needs to review the data and evidence on management performance and determine what changes are needed. This is the feedback stage where results from the first round of adaptive management are considered, and new management is proposed. Changes in management should be larger in early iterations to explore management options rather than refine the current management approach. This can be controversial because for managers it is often safer to continue past practices instead of making large changes and taking risks. However, the advantages of alternative management become apparent when different policies are pursued. The team of managers and scientists learn more by making changes and taking some risks. Also, because the environment is dynamic and uncertain, different options may be informative through time and truly improve management. To be really adaptive, management changes are necessary and fundamental to the learning process.

WHAT MAKES SOME PROJECTS APPROPRIATE FOR ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT?

Environmental problems that are conducive to the adaptive management technique are the ones that are typically viewed as critical and require action. There has to be a mandate for acting on the best course of action under limited knowledge and uncertainty. In other words, the problem must be important enough to require action. These cases have a high learning potential and opportunities to apply learning, and those aspects of adaptive management are seen as promising benefits to long-term management effectiveness. There should also be institutional capacity and commitment, funding to set up a monitoring system, analytic expertise on the team, and experts on the key issues. Key decisions in important cases have to be developed by a thorough and structured process considering a diversity of perspectives. The direction of management needs to be explicitly justified and accountable, and this requires analyses, debate, and consensus building. The management plan adopted has to have clear and measurable objectives and criteria for success. These attributes of ecological conservation support the lead agency or institution because the information, management experience, and success are all highly valued. Engagement of scientific expertise, high-level managers, and financial resources for maintaining the process are vital despite being more costly than top-down administrative decisions. In short, adaptive management is often selected for high profile, complex, costly, and controversial ecological conservation challenges that are being watched by the public, elected officials, and diverse stakeholder groups.

Conversely, there are situations in which adaptive management would not be appropriate. Adaptive management would be difficult to apply in a complex legal environment, in a situation where there are unresolvable conflicts in defining explicit and measurable management objectives or alternatives, where institutional reluctance to change is strong, when risks associated with learning-based decision- making are too high, when decisions that affect resource systems and outcomes cannot be made, and where decision-making occurs only once. Additionally, adaptive management is not appropriate when monitoring cannot provide useful information for decision-making. Monitoring may be ineffective when the frequency of data collection is too low to keep pace with changes in the natural system, there are significant time lags between management actions and their impacts, a monitoring plan cannot be designed to test hypotheses, a firm commitment to funding and institutional support for monitoring is lacking, or when not enough data can be collected to evaluate progress.

IMPLEMENTING ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT

There are three forms of implementation of adaptive management (Walters and Holling 1990; Allan and Curtis 2005). One is evolutionary, or “trial and error,” in which early choices are essentially haphazard, while later choices are made from a subset that gives better results. Second is passive adaptive, where historical data for each time period are used to construct a single, best estimate or model for response, and the decision choice is based on assuming this model is correct. Third is active adaptive, where the data available at each time period are used to structure a range of alternative response-models, and a policy choice is made that reflects some computed balance between expected short-term performance and long-term value of knowing which alternative model is correct.

BENEFITS AND SUCCESSES OF ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT

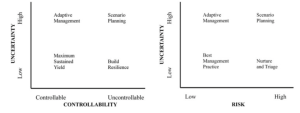

The primary benefits of the adaptive management technique are many. The process encourages long- term collaboration among stakeholders, managers, scientists, and policy-makers (Williams et al. 2009; Williams and Brown 2014). Sharing understanding of the problem and a teamwork setting for finding solutions help to overcome divisions among involved parties. Also, the stakeholders learn management outcomes and the responses of the environmental system. The sharing of perspectives and learning among diverse partners can bring about consensus on management policies that solve conflicts. Acting under uncertainty can be seen as risky, but adaptive management encourages action and has a philosophy that accepts low risk (Figure 11.4) (Allen and Gunderson 2011). The expectation of selecting a management plan with limited information favors learning (Williams et al. 2009). A team effort to explore options and choose a course of management action, forces careful consideration of the objectives, why certain decisions were made, and when results are to be expected. This builds focused decision- making, detailed justifications, and documentation on debates and resolutions (Williams et al. 2009). This also enhances information flow to policy-makers and administrators running complex agencies or organizations. Finally, the concept that management can and should change when more information is available allows decisions to be seen as non-permanent, flexible over time in the face of uncertainty, and iterative (Williams et al. 2009).

Moore et al. (2011) evaluated the success of United States government programs in implementing adaptive management at scales ranging from small, single refuge applications to large, multi-refuge, multi-region projects. Their evaluation suggested three important attributes common to successful implementation: a vigorous multi-partner collaboration, practical and informative decision framework components, and a sustained commitment to the process. Successful application of adaptive management also requires building a thorough understanding of the various elements of the process through cumulative experience (Gerber et al. 2007).

LIMITATIONS IN APPLYING ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT

There are situations where adaptive management is not appropriate. Polarized perspectives on management alternatives, complex litigation settings, legal mandates for specific actions, and institutional reluctance for change may make adaptive management impossible to accomplish. The experimental nature of adaptive management can be another limitation. If there are substantial time lags (e.g., decades) between management actions and system responses, the iterative cycle of adaptive management can be too long. Also, there is a possibility that the environmental setting is rapidly changing, resulting in failed monitoring of the system. Finally, it is possible that the experimentation cannot be properly evaluated because so many confounding factors shape outcomes. These are some examples of situations in which adaptive management can be too difficult to implement and maintain for agencies to support the process.

A key tenet of adaptive management is that collaboration among scientists, managers, and stakeholders results in creative exploration of management options and selection of innovative paths for improved management. However, at times the outcome from a collection of diverse collaborators can stymie truly innovative management options due to the need to achieve consensus across participants. Incompatible perspectives and goals within a group can limit the breadth of considerations and be restrictive of management options. For example, in California, adaptive management of the Sacramento-San Joaquin Bay-Delta did not consider reducing water use by people because it was impossible to reach consensus on this approach (Kallis et al. 2009). Thus tension in collaboration can stifle flexibility, creativity, and adaptability.

A second limitation of collaborative development of management is the temptation to avoid risky options. Basic disagreements on management outcomes among collaborators can limit risk-taking because of the fear of failure. Managers also will be held accountable for failure even though management can be improved by learning and trying new ideas. The process of adaptive management increases transparency in decision-making and adds public and stakeholder attention to management plans. This can elevate the attention on likely management benefits and chances of failure. Many managers avoid bad news coverage, and can resist options debated during the extended experimental period. Adaptive management can be effective for those involved in the process, but for the public the management decisions will require detailed explanations.

Adaptive management can be a costly process. Expenses are generated by ecosystem scale experiments, collaboration, information gathering, modeling, and monitoring. This process takes time and financial resources from agencies, and can be hard to maintain for the long-term, when adaptive management benefits are ultimately realized. Sometimes the adaptive management process is associated with inadequate support, resulting in weak application of science, superficial modeling, and ineffective monitoring. A lead agency can weaken the process for cost and effort reasons, making experimentation and learning less effective across the management options. In practice, adaptive management can miss the mark on the theory of the process and result in a compromised program.

There have been some reviews of adaptive management cases. For example, Walters (1997) investigated 25 adaptive management cases and found only two were effectively executed. Most others ended with no product, little learning, and no improved management. One trap noted was protracted model development and refinement. Overall, there are few adaptive management cases where management was improved by the process. Adaptive management demands fundamental changes in practices and agency operations and an extended period of commitment to realize the gains. New ways of decision- making, information sharing, and learning by experiments take many years of commitment and investment by scientists and managers. Admitting a lack of understanding, the need to learn, and the sharing of information can be difficult for organizations to embrace. Government and agency leadership often changes faster than the time period that the adaptive management process requires. It is often said that history repeats itself, and learning from experience can be slow, unrecognizable, or lost by organizations.

CASE STUDY: GLEN CANYON DAM ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT PROGRAM

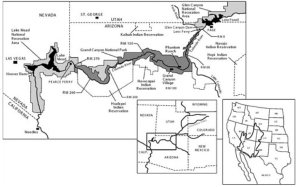

Glen Canyon Dam is directly upstream of Glen Canyon and the Grand Canyon National Park (Figure 11.5). Completed in 1963, this dam and its operations have profoundly changed the nature of the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon and upstream canyons. Scientific evidence gathered during Grand Canyon environmental studies indicated that significant impacts on downstream resources were occurring due to the operation of Glen Canyon Dam. Some of the major effects on the river were cold water temperatures, termination of down river sediment transport, clear water releases, cessation of seasonal high flows and flooding, species endangerment, proliferation of non-native species, dense vegetation cover on shoreline and sand bars, altered channel morphology, and more (Stevens and Waring 1985; Webb et al. 1999). These findings led to a July 1989 decision by the Secretary of the Interior to prepare an environmental impact statement to reevaluate dam operations. The purpose of the reevaluation was to determine specific options that could be implemented to minimize, consistent with law, adverse impacts on the downstream environment and cultural resources, as well as Native American interests in Glen and Grand Canyons. The United States Congress passed the Grand Canyon Protection Act in 1992 with a mandate to modify dam operations to “protect, mitigate adverse impacts to, and improve the downstream resources of the Grand Canyon National Park and the Glen Canyon National Recreational Area” (United States Congress 2021). The Colorado River in the Grand Canyon cannot be fully restored to pre-dam conditions, and there was substantial uncertainty about the environmental and river responses to modified dam operations.

An environmental impact statement was issued in 1995 and included information on beaches, endangered species, ecosystem integrity, fish, power costs, power production, sediment, water conservation, air quality, rafting and boating, and the Grand Canyon as wilderness (United

States Department of the Interior 1995). The United States Secretary of the Interior made a decision to adopt modification of Glen Canyon Dam operations including establishing an adaptive management program (United States Department of the Interior 1995). The adaptive management program was adopted to deal with the uncertainty of dam operations on the canyon environments (Wieringa and Morton 1996). Also, the program was implemented to conduct management experiments to fulfill obligations under the Grand Canyon Protection Act. Experimental dam operations, long-term monitoring, and extensive research on options for additional dam operation modifications were seen as necessary. Environmental commitments made by the Secretary also included building beaches and habitats with flow events, protection of cultural resources, increasing flood frequency, and recovery of the endangered humpback chub (Gila cypha). The adaptive management program was charged with:

5. Integrate new knowledge and information in management options and recommendations to the United States Secretary of the Interior.The tasks identified for this adaptive management program are very consistent with the concept of adaptive management. Also, this case shares many attributes of feasible adaptive management cases because of its importance, long-term investment, and high-level government support.

The Adaptive Management Work Group was appointed by the United States Secretary of the Interior with representatives of the federal agencies, states, Native American tribes, environmental conservationists, recreational organizations, and electric power user groups. This Work Group led the adaptive management program for protecting and mitigating adverse impacts to the Grand Canyon National Park and the Glen Canyon National Recreational Area. The responsibilities of the Adaptive Management Work Group were to annually review monitoring data and hypothesis tests to determine if objectives were being attained, develop recommendations to the United States Secretary of the Interior for modifying dam operations, and facilitate input from interested parties. Issues of interest spanned natural canyon properties like open beaches and shorelines and the recovery of endangered species as well as non-natural features like the trout fishery below Glen Canyon dam. Therefore, the Adaptive Management Work Group had to develop management options for a novel ecosystem and consider human uses of the National Park and National Recreational Area.

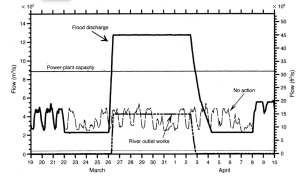

A prominent modification of Glen Canyon dam operations promoted by the Adaptive Management Work Group was periodic controlled floods. An experimental flood was conducted in 1996 with an increased water release of 1,274 m3/s from the dam for seven days (Figure 11.6). The test flood was needed to test the hypothesis that the dynamic nature of fluvial landforms and aquatic and terrestrial habitats can be wholly or partially restored by short-duration dam releases substantially greater than power-plant capacity. This controlled flood was predicted to restore open sandy beach, scour riparian vegetation, and create shoreline nursery habitats for an endangered fish. The controlled flood was recognized as much smaller than pre-dam floods that ranged from 3,000 to 8,500 m3/s. Field studies were executed to test predictions of environmental benefits from restoring flood flows to the canyon. This modification of dam operations succeeded in building sandbars by moving sediments from the channel to the river shorelines, creating higher but not wider sandbars (Figure 11.7) (Collier et al. 1997). Sediment buried some riparian vegetation but was insufficient to scour perennial riparian vegetation, especially woody species. There was no detectable harm on endangered species, but there were clear improvements for recreational rafters because of new camping beaches (Stevens et al. 2001). Lake Powell above the dam dropped 1.1 m and $2.5 million in hydropower revenue was lost (Patten et al. 2001). Research costs were $1.5 million for a total financial investment in this operational modification of about $4.0 million (Patten et al. 2001).

The conclusions of the controlled flood experiment were that restoring high flows to the canyon altered the ecosystem in beneficial ways, improved understanding of varying flow rates, and that high flow periods (part of the natural flow regime) should be part of the operations of the dam. The 1996 controlled flood received substantial press coverage, and now this practice has been implemented on many rivers throughout the world and again from the Glen Canyon dam with different river volumes and durations (Figure 11.8) (Melis et al. 2010; Topping et al. 2010; United States Department of the Interior 2011; Yao and Rutschmann 2015). Monitoring data and hypothesis tests improved sediment modeling, and this improvement allowed managers to determine the best frequency, timing, duration, and magnitude for future controlled floods. Varying the specifications for controlled floods is an example of enhanced management actions being developed by the adaptive management process.

Integration of knowledge and perspectives by scientists and managers is fundamental to improving decisions under adaptive management. The Adaptive Management Work Group included scientists that are experts in fields important to Grand Canyon issues. That built credibility for expensive and novel dam operation changes. Managers engaged in Grand Canyon issues pressed scientists to be focused on management needs. Monitoring and hypothesis testing of new dam operations enabled managers to learn how modifications of dam operations could influence ecosystem properties. The controlled floods illustrated how science, modeling, and public use of the Grand Canyon were combined to change dam operations. The diverse Adaptive Management Work Group dealt with difficult trade-offs and reached a compromised strategy that improved management. This was seen from the cooperation and planning involved in the flood events as they were a big departure from standard dam operations and involved working with special interest groups that were strongly resistant to change. Developing consensus among stakeholders on the use of scientific information and managed floods for sediment and resource management remains a primary challenge to the Adaptive Management Work Group.

Commonly, with formal environmental impact assessments under the National Environmental Protection Act, the adoption of the preferred management alternative is viewed as a “forever” decision. The Department of Interior’s 1995 impact statement included adaptive management in the final decision. This inclusion opened the way for modifying dam operations through time to improve the Grand Canyon ecosystem and allow for management flexibility with new knowledge. It also allowed science, monitoring, and hypothesis testing to continue with the purpose of improving both management and the ecosystem. The experimental results from the Glen Canyon Dam program represent scientific successes in terms of revealing new opportunities for developing better river management policies (Melis et al. 2015). This is a case where a United States national treasure was degrading and Congress acted to mandate that the impacts on it be mitigated and the ecosystem improved.

SUMMARY

In truly important cases, like the Glen Canyon Dam reviewed here, all of the adaptive management program attributes were implemented in a manner that matched the concept of adaptive management: assessing the problem, predicting outcomes based on current information, implementing a plan, monitoring the outcome, evaluating success or failure, and adjusting management actions. There are few cases like this; many applications of adaptive management have failed (McLain and Lee 1996). However, when the government and agency investment in the process is significant, it appears that the benefits of adaptive management can succeed over time and truly improve holistic ecological conservation (Bormann et al. 2007).

REFERENCES

Allan, C. and Curtis, A., 2005. Nipped in the bud: why regional scale adaptive management is not blooming. Environmental Management, 36(3), pp.414-425.

Allen, C.R., Fontaine, J.J., Pope, K.L. and Garmestani, A.S., 2011. Adaptive management for a turbulent future. Journal of environmental management, 92(5), pp.1339-1345.

Allen, C.R. and Gunderson, L.H., 2011. Pathology and failure in the design and implementation of adaptive management. Journal of environmental management, 92(5), pp.1379-1384.

Boesch, D. F., and the National Research Council Panel on Adaptive Management for Resources Stewardship, 2004. Adaptive management for water resources planning. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC.

Bormann, B.T., Haynes, R.W. and Martin, J.R., 2007. Adaptive management of forest ecosystems: Did some rubber hit the road? BioScience, 57(2), pp.186-191.

Collier, M.P., Webb, R.H. and Andrews, E.D., 1997. Experimental flooding in Grand Canyon. Scientific American, 276(1), pp.82-89.

Delta Stewardship Council, 2019. Delta Conservation Adaptive Management Action Strategy. Available: https://www.deltacouncil.ca.gov/pdf/science-program/2019-09-06-iamit-strategy-april-2019.pdf (September 2021).

Dreiss, L.M., Hessenauer, J.M., Nathan, L.R., O’Connor, K.M., Liberati, M.R., Kloster, D.P., Barclay, J.R., Vokoun, J.C. and Morzillo, A.T., 2017. Adaptive management as an effective strategy: Interdisciplinary perceptions for natural resources management. Environmental management, 59(2), pp.218-229.

Gerber, L.R., Wielgus, J. and Sala, E., 2007. A decision framework for the adaptive management of an exploited species with implications for marine reserves. Conservation Biology, 21(6), pp.1594-1602.

Great Lakes Phragmites Collaborative, 2016. Introducing the Phragmites Adaptive Management Framework (PAMF) Initiative. Available: https://www.greatlakesphragmites.net/blog/introducing-the- phragmites-adaptive-management-framework-pamf-initiative/ (September 2021).

Haney, A. and Power, R.L., 1996. Adaptive management for sound ecosystem management. Environmental management, 20(6), pp.879-886.

Holling, C.S., 1978. Adaptive environmental assessment and management. John Wiley & Sons, New York, New York.

Johnson, B.L., 1999. The role of adaptive management as an operational approach for resource management agencies. Conservation ecology, 3(2).

Kallis, G., Kiparsky, M. and Norgaard, R., 2009. Collaborative governance and adaptive management: Lessons from California’s CALFED Water Program. environmental science & policy, 12(6), pp.631- 643.

Kato, S. and Ahern, J., 2008. “Learning by doing”: Adaptive planning as a strategy to address uncertainty in planning. Journal of environmental planning and management, 51(4), pp.543-559.

McFadden, J.E., Hiller, T.L. and Tyre, A.J., 2011. Evaluating the efficacy of adaptive management approaches: Is there a formula for success? Journal of environmental management, 92(5), pp.1354- 1359.

McLain, R.J. and Lee, R.G., 1996. Adaptive management: Promises and pitfalls. Environmental management, 20(4), pp.437-448.

Medema, W., McIntosh, B.S. and Jeffrey, P.J., 2008. From premise to practice: a critical assessment of integrated water resources management and adaptive management approaches in the water sector. Ecology and Society, 13(2).

Melis, T.S., Topping, D.J., Grams, P.E., Rubin, D.M., Wright, S.A., Draut, A.E., Hazel Jr, J.E., Ralston, B.E., Kennedy, T.A., Rosi-Marshall, E. and Korman, J., 2010. 2008 High-Flow Experiment at Glen Canyon Dam Benefits Colorado River Resources in Grand Canyon National Park. United States Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 2010-3009, Grand Canyon Monitoring and Research Center, Flagstaff, AZ.

Melis, T.S., Walters, C.J. and Korman, J., 2015. Surprise and opportunity for learning in Grand Canyon: The Glen Canyon dam adaptive management program. Ecology and Society, 20(3).

Moore, C.T., Lonsdorf, E.V., Knutson, M.G., Laskowski, H.P. and Lor, S.K., 2011. Adaptive management in the United States National Wildlife Refuge System: Science-management partnerships for conservation delivery. Journal of Environmental Management, 92(5), pp.1395-1402.

Patten, D.T., Harpman, D.A., Voita, M.I. and Randle, T.J., 2001. A managed flood on the Colorado River: Background, objectives, design, and implementation. Ecological Applications, 11(3), pp.635- 643.

Smith, C.B., 2011. Adaptive management on the central Platte River–science, engineering, and decision analysis to assist in the recovery of four species. Journal of Environmental Management, 92(5), pp.1414-1419.

Stevens, L.E. and Waring, G.L., 1985. The effects of prolonged flooding on the riparian plant community in Grand Canyon. Riparian ecosystems and their management—reconciling conflicting uses. USDA Forest Service General Technical Report RM-120, Washington, DC, pp.81-86.

Stevens, L.E., Ayers, T.J., Bennett, J.B., Christensen, K., Kearsley, M.J., Meretsky, V.J., Phillips III, A.M., Parnell, R.A., Spence, J., Sogge, M.K. and Springer, A.E., 2001. Planned flooding and Colorado River riparian trade‐offs downstream from Glen Canyon Dam, Arizona. Ecological Applications, 11(3), pp.701-710.

Topping, D.J., Rubin, D.M., Grams, P.E., Griffiths, R.E., Sabol, T.A., Voichick, N., Tusso, R.B., Vanaman, K.M. and McDonald, R.R., 2010. Sediment transport during three controlled-flood experiments on the Colorado River downstream from Glen Canyon Dam, with implications for eddy-sandbar deposition in Grand Canyon National Park. United States Geological Survey Open-File Report, 1128, p.111.

United States Congress, 2021. S.387 – Grand Canyon Protection Act. Available: https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/387 (September 2021).

United States Department of the Interior, 1995. Operation of Glen Canyon Dam: Colorado River storage project, Arizona – Final Environmental Impact Statement. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation, Washington, DC.

United States Department of the Interior, 2011. Development and implementation of a protocol for high-flow experimental releases from Glen Canyon Dam, Arizona, 2011 through 2020. Draft Environmental Assessment, Department of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Walters, C.J., 1986. Adaptive management of renewable resources. Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

Walters, C.J., 1997. Challenges in adaptive management of riparian and coastal ecosystems. Conservation ecology, 1(2).

Walters, C.J. and Holling, C.S., 1990. Large-scale management experiments and learning by doing. Ecology, 71(6), pp.2060-2068.

Webb, R.H., Wegner, D.L., Andrews, E.D., Valdez, R.A. and Patten, D.T., 1999. Downstream effects of Glen Canyon dam on the Colorado River in Grand Canyon: A review. Washington DC American Geophysical Union Geophysical Monograph Series, 110, pp.1-21.

Wieringa, M.J. and Morton, A.G., 1996. Hydropower, adaptive management, and biodiversity. Environmental management, 20(6), pp.831-840.

Williams, B.K., Szaro, R.C. and Shapiro, C.D., 2009. Adaptive management: The United States Department of the Interior technical guide. United States Department of the Interior, Washington, DC.

Williams, B.K. and Brown, E.D., 2014. Adaptive management: From more talk to real action. Environmental Management, 53(2), pp.465.

Woods, P.J., 2021. Aligning integrated ecosystem assessment with adaptation planning in support of ecosystem-based management. ICES Journal of Marine Science.

Yao, W. and Rutschmann, P., 2015. Three high flow experiment releases from Glen Canyon Dam on rainbow trout and flannelmouth sucker habitat in Colorado River. Ecological Engineering, 75, pp.278- 290.