9 Chapter Nine: A Health Equity Lens in Obesity Related Chronic Disease Prevention Programs

Authored by: Sara A. Elnakib, PhD, MPH, RDN; Edited by Sherri M. Cirignano, MS, RDN, LDN

Chapter Outline

Introduction

What is Health Equity?

Health Equity

Social Determinants of Health

Why Health Equity Matters?

Health Disparities and Inequities

Health Disparities in Obesity

Conceptual Framework for a Health Equity Approach

What is the Social Ecological Model (SEM)

Focusing on Health Equity in Program Planning, Design & Evaluation

Assess Needs

Developing Partnerships

Developing an Intervention

Implementing and Monitoring the Intervention

Evaluating and Disseminating the Results

Sustaining the Efforts.

- Summary

- Critical Thinking Questions

- Resources

- References

Introduction

Throughout this book you have learned about the impact of obesity on individuals, and the connection between chronic disease and obesity. You have also learned about evidence-based interventions that can reduce obesity and improve health both on an individual level as well as a community level. The need to modify programs to support program participants from diverse backgrounds has been infused throughout the chapters. However, in this chapter we will be making the case for why a health equity lens is a necessary construct in any obesity related chronic disease prevention program. Understanding the underlying issues of health disparities, the systems that have put them in place and the impacts they have had on historically marginalized populations is necessary to develop truly impactful programs. To do this we will define health equity and explain why it matters, the conceptual framework that underlies a health equity approach and finally what can be done in program planning, design, and evaluation to ensure that programming has a health equity lens.

What is Health Equity?

For many years health education has been focused on individual choice, framing health as a personal responsibility where good health is considered a personal success and poor health a personal failure.1 However, this limited focus on individual health behaviors ignores the contextual factors that have a much larger impact on health. Imagine you are developing a program to promote fruit and vegetable consumption in a specific population. You can develop an evidenced based program, with accurate statistics and innovative ideas, but if your target population does not have access to fruits and vegetables, you will never reach your behavioral objective of increasing fruit and vegetable intake. Without addressing the social, institutional, and environmental factors that may influence your target populations direct behavior change, you will have a limited impact on their health.

Health Equity

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “Health equity is achieved when every person has the opportunity to “attain his or her full health potential” and no one is “disadvantaged from achieving this potential because of social position or other socially determined circumstances”.2 This definition indicates that ?there are individuals who may be disadvantaged by a non-health related social factor. The United Nation’s World Health Organization expands on this definition suggesting that health equity is the “absence of avoidable, unfair, or remediable differences among groups of people, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, demographically or geographically or by other means of stratification”.3 The United Nation’s World Health Organization definition explicitly highlights the fact that these inequities are avoidable and therefore solvable. The definition also indicates that the way resources are often provided or denied is based on factors that can be evaluated such as demographic, economic, and geographic factors. In a National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine report on pathways to health equity, the authors unambiguously indicated factors such as “race, ethnicity, gender, employment and socioeconomic status, disability, immigration status, and geography”4 as influencers of health equity.

Social Determinants of Health

Factors that influence health outside of biological factors are also called social determinants of health. According to the World Health Organization social determinants of health are the “complex, integrated, and overlapping social structures and economic systems that are responsible for most health inequities. These social structures and economic systems include the social environment, physical environment, health services, and structural and societal factors. Social determinants of health are shaped by the distribution of money, power, and resources throughout local communities, nations, and the world”.5 Expanding our focus beyond individual behavior to include social determinants of health allows for a shift towards more “upstream” action that is the basis of public health interventions. This realization of how social factors and conditions in which we live, learn, work and play can shape our disease morbidity and mortality is a powerful realization. These conditions are shaped by policies, laws, investment, and cultural norms that have been influenced by structural racism. To support health equity, we need to address the system as a whole to “eliminate structural racism, reduce poverty, improve income equality, increase educational opportunity, and fix the laws and policies that perpetuate structural inequities”4.

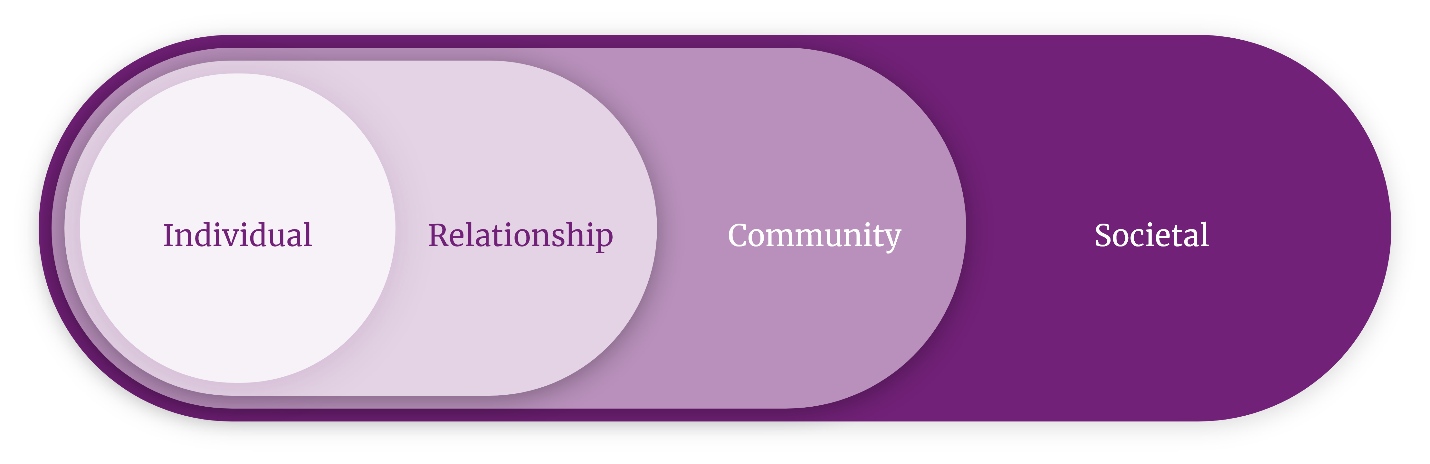

In figure 1, Cooperative Extension proposes a health equity and wellbeing framework that takes into consideration these social determinants of health.6 As discussed in chapter 6, Cooperative Extension (CE) is the outreach arm of the Land Grant Universities, and the Department of Family and Consumer (or Community Health) Sciences is tasked with developing programs to support improved health in the community. In order to do that CE explicitly identifies the root causes of structural inequalities highlighting issues such as ableism, ageism, xenophobia, racism, homophobia, classism and sexism that have impacted our norms, policies and practices that have created inequity in our communities.6 These inequities can be seen in social determinates of health such as access to quality housing, food and transportation, how the physical environment is set up, and inequities in education, income, and employment. By framing CE programing with these larger issues in mind, CE professionals can identify health inequities and promote healthy behaviors through collective action.6

Why Health Equity Matters?

Health Disparities and Inequities

According to the definition of health equity, there may be health differences between groups in a population which are linked to social, economic, or environmental disadvantages. These differences are called health disparities. Health disparities can be “differences in length of life; quality of life; rates of disease, disability, and death; severity of disease; and access to treatment”.2,7 We can find health disparities linked to chronic diseases such as diabetes, stroke, heart disease, cancer and obesity.8 These disparities can be seen when segmenting the population by race or ethnicity9, geography10, income11 and gender along with other factors. In order to address these disparities, we need to assess how these disparities impact the population we are interested in and then evaluate what interventions can be used to support the desired behavior change in the population.

Health Disparities in Obesity

While there is consensus among scientists of the biological and genetic factors that influence obesity, there is a growing body of evidence indicating that there are many social, environmental and economic factors that influence obesity.7 For example, we understand that obesity is a result of excess energy intake and limited energy expenditure, however the availability of energy dense foods and limited access to safe places to be physically active in a neighborhood may have a direct impact on an individual’s likelihood of becoming obese. In fact, these factors have been recognized as “built environment” elements that can either facilitate or prevent obesity.7 Research has shown that the presence of food deserts, an area with limited supermarkets and food swamps, an area with abundant fast food and convenience stores but limited supermarkets, can predict obesity rate.7,12 Research indicates that food deserts and food swamps are predominately present in low-income communities.12 Additionally, research has shown that neighborhood safety has a statistically significant impact on childhood BMI rates.13 This indicates that children living in unsafe, low income communities are more likely to develop obesity irrespective of personal choice due to the built environment. This reality can be seen through the stratification of obesity data across different social factors.

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) has been used to assess obesity across the US over time, which the CDC publishes in state-specific maps since 1999.14 State-specific prevalence ranges from a low of 22.6% in Colorado to a high of 38.1% in West Virginia. However, when stratifying the data by race and ethnicity there is a trend where black adults had the highest prevalence of obesity (38.4%) overall, followed by Hispanic adults (32.6%) and white adults (28.6%).14 According to the CDC, racial and ethnic disparities in obesity risk are present as early as the age of 2 years old.14,15 Figure 2 shows the states with the highest burden of obesity (35% or more) by adults’ race and ethnicity. In this figure it is apparent that black adults have the highest burden of obesity in 31 states and the District of Columbia compared to only 8 states among Hispanic adults, and only 1 state among white adults.14

|

Figure 2: Obesity prevalence by state for black, Hispanic, and white adults in the United States |

|

|

Source: https://www.cdc.gov/pcd/issues/2019/18_0579.htm |

As we understand the different social factors that influence obesity, these health disparities need to be prioritized in the prevention and treatment of obesity and chronic diseases. However, understanding the theoretical framework in which all these factors connect is an important first step in developing prevention and treatment programs with a health equity lens.

Conceptual Framework for a Health Equity Approach

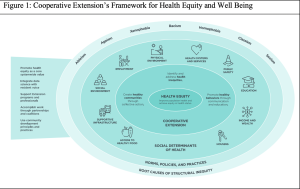

As interventions move from a person centric approach to a public health approach there are many factors to consider. In an effort to organize these factors and their interactions, researchers have used the Social-Ecological Model. 16 The Social-Ecological Model is built on the premise that a person’s health status is influenced by physical, social and cultural dimensions and that the same environment may have different effects based on an individual’s financial resources. 16 It also considers that an individual is dynamic and operates in multiple environments including where they live, learn, work or play. 16 These environments may be a way to influence a person’s behavior.16 Figure 3 displays the four concentric circles that make up the different levels of the Social-Ecological Model. The first level is the individual factors that impact a person’s health. These are factors specific to the person, including their age, gender, education, income and health history. The second level describes the relationship factors that may influence behavior. This may include a persons’ family, friends, and partners. The third level specifies the community level influences, and that community can be defined in many ways. it could be their neighborhood or other physical characteristics that relate to a setting, such as their school or workplace. Finally, the last level portrays the Societal level which includes social norms, and policies that impact health.

|

Figure 3: The Social-Ecological Model: A Framework for Prevention |

|

|

Source: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/social-ecologicalmodel.html |

Clarifying the relationship between an individual and the many factors that influence their behavior can help community health interventions target different factors to ensure improved health outcomes. This framework continues to reinforce the idea that these social determinants of health have a much bigger impact on health than an individual’s health behaviors.

Focusing on Health Equity in Program Planning & Evaluation

Assess Needs

The first step to ensuring an intervention program has a health equity lens is to assess the data. Both quantitative and qualitative data can be collected to assess the disease burden of obesity in different groups. As mentioned earlier, the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) has been used to assess obesity across the US over time, this data is publicly available and can be used to measure obesity in specific populations over time. Quantitative data should be stratified by the different social determinants of health to assess if a health disparity is present.7 The County Health Rankings and Roadmaps, a program of the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute, provides data on different social determinants of health for all counties in the United States, and can be used to highlight geographic disparities.17 Qualitative data on the barriers to certain health behaviors can help identify the underlying social determinants of health that need to be addressed to improve health outcomes.

Developing Partnerships

Assuming that health education professionals have all the answers can create a major issue when working with the community. Partnering with community-based organizations as well as community members can only make the obesity program stronger. Having partners will allow for sharing of resources such as staff, time and money for implementing the program. It also provides a greater likelihood of success and sustainability for the program since partners are included from the beginning of the program planning process. Deciding on which partners to engage will depend on the type of intervention program and which social determinants of health factors the program will address.

Developing an Intervention

Using the data from the earlier steps and directly working with the community, one can collectively develop an intervention that is evidence based. Use the data from the assessment to decide which population to work with. Identify the health disparities that are present in that community and which social determinant of health the intervention will focus on. Once the intervention outcome has been determined, and the evidence-based policy, systems, or environmental changes have been researched and prioritized, the focus can then be on the desired outcome. This can be achieved by using a logic model to ensure each of the components of the intervention is outlined and will help plan the intervention more effectively. Working closely with community partners to design the intervention and communication plan, is essential. Additionally, communicating the results of the work to program participants as well as identified stakeholders needs to be included in the intervention plan.

Implementing and Monitoring the Intervention

Ensuring that the program goes according to plan is an important next step. Monitoring and collecting data on who is participating in the program, how the goals of the program are being met through the activities undertaken and checking in with the community partners will ensure the program is implemented in the way that it was planned. There are many different evaluation tools that can be used to assess that the implementation of the intervention stays true to it’s intended process. A process evaluation reviews the program activities and compares them with the plan to assess if the program was delivered correctly.

Evaluating and Disseminating the Results

The field of health equity is still an emerging field, and in need of robust evaluation of policy, systems and environmental changes on positive health outcomes. Evaluation of the program to assess its impact on positive health outcomes is needed to develop and add to evidenced based solutions for health equity. Analyzing the data collected can contribute to the progress of the health equity field and obesity prevention and control. Focusing on the specific social determinates of health issues the intervention addressed, for which populations in what ways can help the entire field understand what we can collectively do to improve health disparities. Sharing the results with the scientific community through journal manuscripts, poster presentations and academic lectures should be part of the dissemination strategy. Translating the findings into easily understood factsheets and articles for stakeholders will ensure they not only recognize what was done but also ensure they can spread the word on the findings. Additionally, writing about the findings and their broader impacts in news media, social media and other public outlets can help move the conversation about health equity forward.

Sustaining the Efforts.

Sustaining the program needs to be considered from the very beginning of the planning process. That is why in the developing partnerships section sustainability was a consideration. Programs that have policy, systems and environmental changes tend to have sustainability embedded into them because of the nature of these changes. However, support from coalitions and the target audiences can help ensure that these changes last. Empowering the people who are touched by these changes to speak up when policy or systems aren’t being upheld can help ensure sustainability of the initiative. Additionally, many of these efforts need to adapt to the changes in the community, political environment and funding streams. That is why working with coalitions and developing partnerships can create internal accountability and a collective approach to problem-solving.

Summary

This chapter highlighted the impact of health disparities on different populations. Stratifying data to understand how different populations are impacted by different disease states can help identify health disparities. Using the social determinants of health framework to understand the social structures and economic systems that may underpin these disparities can help health educators find solutions that are sustainable and effective. Additionally, understanding that individual behavior is impacted by many factors and there are many models and frameworks that try to explain individual behavior. The Social Ecological model can be used to understand how to move programs from a person centric approach to a public health approach that may impact more people and have a sustainable impact. Finally, the chapter outlined considerations for program planning, design, implementation and evaluation to ensure that obesity prevention and control programs have a health equity lens to reduce health disparities in obesity.

Critical Thinking Questions

- What are a few health disparities that impact obesity in the United States?

- How are some ways to ensure an obesity prevention program has a health equity lens?

- Identify and explain the core components of the social ecological models of health behavior.

Resources

CDC’s Health Equity Resource Toolkit for State Practitioners Addressing Obesity Disparities

Prioritizing Nutrition Security: Cooperative Extension’s Framework for Health Equity and Well-Being

CDC’s Logic Models Approach to Evaluation

The Health Equity Assessment Tool: A User’s Guide

References

- Temmann LJ, Wiedicke A, Schaller S, Scherr S, Reifegerste D. (2021) A Systematic Review of Responsibility Frames and Their Effects in the Health Context. J Health Communication. 2021. 26(12): 828-838. DOI: 10.1080/10810730.2021.2020381

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Health Equity. Accessed March 2023.

- https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/healthequity/index.htm

- World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health. Accessed March 2023. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Communities in Action: Pathways to Health Equity. The National Academies Press: Washington, DC. Accessed March 2023. https://www.nap.edu/read/24624/chapter/1

- World Health Organization. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health – final report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Accessed March 2023. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-IER-CSDH-08.1

- Burton et al. Cooperative Extension’s National Framework for Health Equity and Well Being. [Report of the Health Innovation Task Force] Extension Committee on Organization and Policy: Washington, DC. Accessed March 2023. https://www.aplu.org/members/commissions/food-environment-and-renewable-resources/board-on-agriculture-assembly/cooperative-extension-section/ecop-members/ecop-documents/2021%20EquityHealth%20Sum.pdf

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Nutrition, Physical Activity and Obesity with Stephen James, Lisa Hawley, Rachel Kramer, and Yvonne Wasilewski at SciMetrika, LLC. Health Equity Resource Toolkit for State Practitioners Addressing Obesity Disparities. Accessed March 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/health-equity/state-health-equity-toolkit/pdf/toolkit.pdf

- Thorpe KE, Chin KK, Cruz Y, Innocent MA, Singh L. The United States Can Reduce Socioeconomic Disparities By Focusing On Chronic Diseases. Health Affairs. August 17, 2017. DOI: 10.1377/hblog20170817.061561

- Price JH, Khubchandani J, McKinney M, Braun R. Racial/ethnic disparities in chronic diseases of youths and access to health care in the United States. Biomed Res Int. 2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/787616

- National Institute of Health. National Library of Medicine. Challenges and Successes in Reducing Health Disparities: Workshop Summary. The Impact of Geography on Health Disparities in the United States: Different Perspectives. 2008. Accessed March 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK215365/

- Chokshi DA. Income, Poverty, and Health Inequality. JAMA. 2018;319(13):1312–1313. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.2521

- Cooksey-Stowers K, Schwartz MB, Brownell KD. Food Swamps Predict Obesity Rates Better Than Food Deserts in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2017. 14; 1366. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14111366

- Hilmers A, Hilmers DC, Dave J. Neighborhood disparities in access to healthy foods and their effects on environmental justice. Am J Public Health. 2012. Sep;102(9):1644-54. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300865

- Petersen R, Pan L, Blanck HM. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Adult Obesity in the United States: CDC’s Tracking to Inform State and Local Action. Prev Chronic Dis. 2019;16:180579. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd16.180579

- Pan L, Freedman DS, Sharma AJ, Castellanos-Brown K, Park S, Smith RB, et al. Trends in obesity among participants aged 2–4 years in the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children — United States, 2000–2014. MMWR. 2016. 65(45):1256–60.

- Stokols D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. Am J Health Promo. 1996. 10(4):282–298. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.282

- County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. Accessed March 2023. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/