8 Chapter Eight: Cancer and its Relationship to Obesity

Authored by: Sherri M. Cirignano, MS, RDN, LDN

History of the Link Between Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer

Cancer Overview

Types of Cancer

Cancer Rates

United States

New Jersey

Energy Balance, Body Fatness and the Risk of Cancer

WCRF/AICR Diet, Nutrition and Physical Activity Recommendations for the Prevention of Cancer

American Cancer Society Guideline for Diet and Physical Activity for Cancer Prevention

Summary

Resources

References

History of the Link Between Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer

The first mention of food and nutrition and their link to cancer dates to as early as the time of the Song Dynasty in China from 960-1279 AD when Yong-He-Yan, a physician of the time, believed that poor nutrition was the cause of esophageal cancer.1 In the 17th century Dr. Richard Wiseman, a British surgeon, believed that cancer might arise ‘from an error in diet’ and advised abstention from ‘salt, sharp and gross meats.’2 In more recent history, laboratory studies on animals, known as in vivo studies, in the 1930’s revealed a possible influence of diet on cancer development. This led to population studies, the results of which were first presented in the 1970’s, igniting rapid development in this field and furthering the knowledge we have today on the link between what we eat and the disease of cancer.1 Although the importance of the link between nutrition and cancer has been recognized for centuries, the more robust study of it is still considered to be in its early years.

As with nutrition, the relationship between physical activity and health have been documented since ancient times. ‘Eating alone will not keep a man well; he must also take exercise. For food and exercise, while possessing opposite qualities, yet work together to produce health…’ Hippocrates, ‘the father of medicine’ said this, and although it is not specifically about cancer prevention, this proposed role of physical activity in health promotion first appeared as early as the 2nd century.3 The role of physical activity specific to cancer prevention was explored in the 1920’s with the publication of two studies that suggested that “cancer mortality rates among men with different occupations decreased with increased physical activity.”4 Since that time, many studies have explored the role of physical activity and cancer prevention with “substantial evidence” that increased physical activity can lower the risk of certain cancer types.4

Please click the above link for this topic.

Please click the above link for this topic.

Cancer Rates

United States

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the United States, just behind heart disease, the leading cause of death in the United States. In 2019, the latest year for which cancer incidence data are available in the United States, over 1.7 million new cases of cancer were reported, and close to 600,000 people died of cancer. For every 100,000 people, 439 new cancer cases were reported and 146 people died of cancer.7

The top four cancer types in the US by rates of new cancer cases of male and female, (all races and ethnicities) are: 1) female breast cancer; 2) prostate cancer; 3) lung and bronchus cancers; and 4) colon and rectal cancers. The top five cancers by rates of cancer deaths for males and females, (all races and ethnicities) are: 1) lung and bronchus cancers; 2) female breast cancer; 3) prostate cancer; 4) colon and rectal cancers; and 5) cancer of the pancreas.8

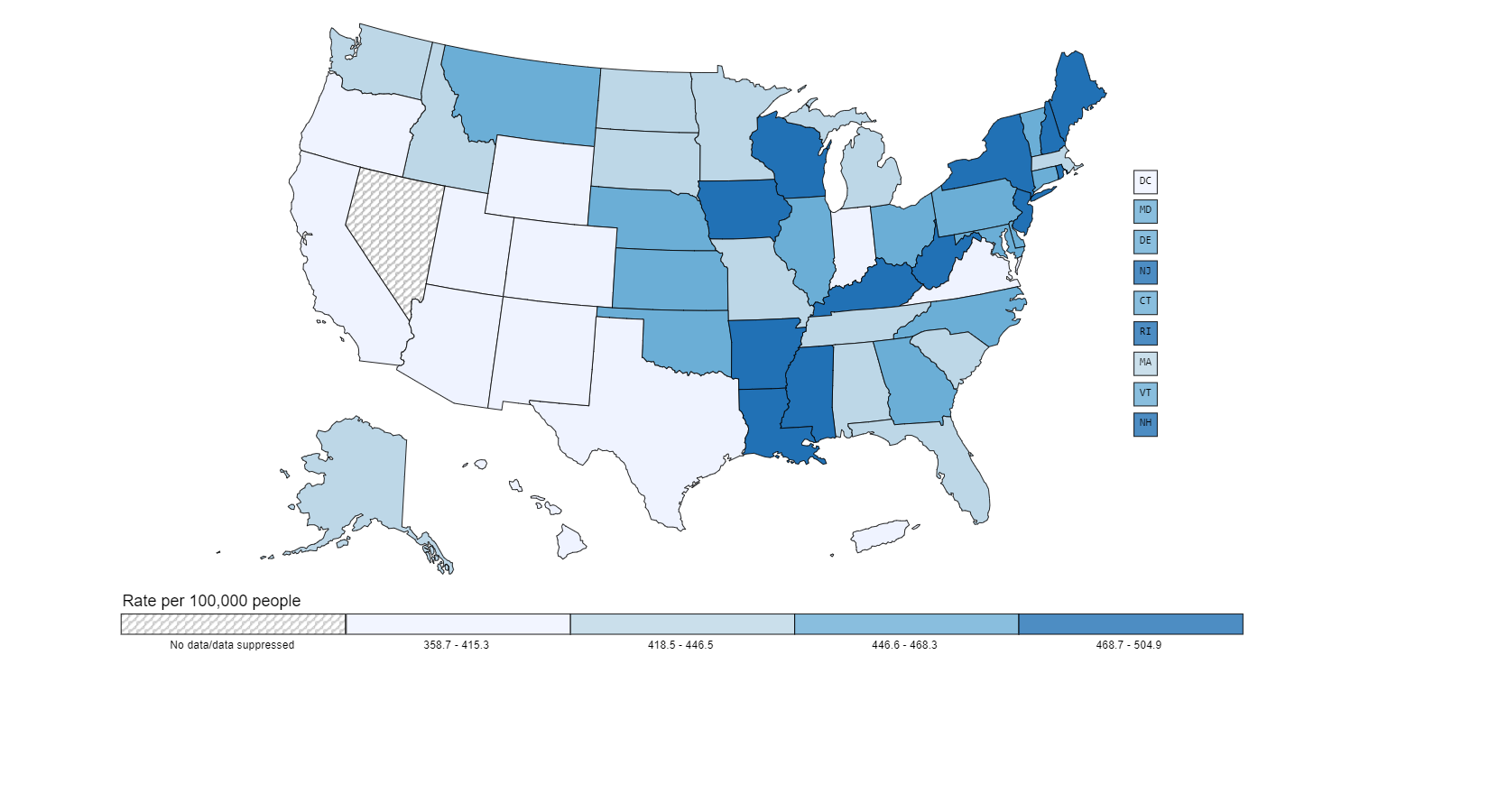

In addition to looking at the color-coded map seen in Figure 1 below, with the darkest color showing where the most incidence or rate of cancer is found, you can find out more information about the state where you live by going to the CDC site Cancer Statistics at a Glance.

New Jersey

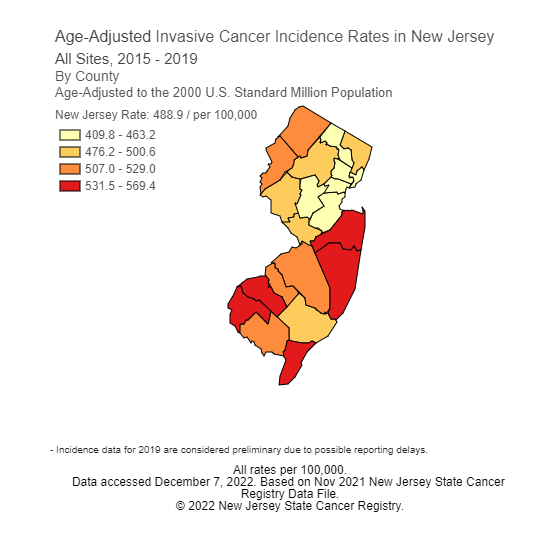

In NJ, rates of cancer are highest in the southern counties and the northeastern corner of the state. The darker the color of a county, seen in the map below in Figure 2, indicates a higher incidence or rate of cancer in that county. The following are facts about the age-adjusted incidence cancer rates in NJ from the National Cancer Institute and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:9 (CDC)

All stages of cancer are higher in NJ than the incidence rates for the United States as a whole.

The leading cancer site for NJ women, and a leading cause of death, is breast cancer. The incidence rate for female breast cancer is also higher in NJ than the incidence rates for the United States as a whole.

The leading cancer site for NJ men is prostate cancer. And, similar as for women and breast cancer, the incidence rate for prostate cancer is also higher in NJ than the incidence rates for the United States as a whole.

The leading cancer sites in NJ are prostate cancer and female breast cancer.

The leading age-adjusted mortality rates by cancer site in NJ are 1) lung and bronchus; 2) female breast; 3) prostate; and 4) colon and rectum.

Energy Balance, Body Fatness and the Risk of Cancer

Several national and global organizations work to research cancer and to decrease its prevalence and educate the public about specific links towards cancer prevention. The World Cancer Research Fund (WCRF) and the American Institute for Cancer Research (AICR) are two organizations that join approximately every ten years to create a global report on the “very latest research, findings and cancer prevention recommendations.”10 Prior reports were released in the 1990’s and again in 2007. The newest and Third Expert Global Report by the WCRF/AICR, Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: a Global Perspective was presented in 2018. The Report is created by a distinguished panel of experts who undergo a comprehensive review of the literature to judge all available evidence on “preventing and surviving cancer” with which they determine and present the latest recommendations on diet, nutrition and physical activity. Between additions of the Report, there is continuous work being completed by these two organizations through the Continuous Update Project. The CUP is an ongoing program that analyzes global research on how diet, nutrition and physical activity affect cancer risk and survival.11

According to the WCRF/AICR 2018 Report, there are several cancer sites that are linked to overweight and obesity, termed “body fatness” in the Report. As a result, maintenance of a healthy body weight throughout life is recommended to work towards prevention of these cancer types. An important step in achieving a healthy body weight includes attaining energy balance. Energy balance is the ability to match the intake of energy through the consumption of food and beverages with the output of energy through normal bodily functions and physical activity.

Energy balance is regulated by internal factors such as appetite, genetics, fetal weight and potentially even the bacteria from the colon, known as the gut microbiome. External stimuli that can affect energy balance can include factors such as stress, eating disorders, economic factors and the circumstances in which the food is being consumed.12

If there is an excess of energy consumed from food and beverages, the body stores it as fat in adipose tissue. How much fat is accumulated and where the body stores it in the body is somewhat individual. It can be stored around our organs or muscles or within tissues such as the liver.12 This is mostly determined by genetic factors including gender. Women are known to mostly store more fat around their hips, buttocks and thighs than men resulting in a ‘pear shape’ and the distribution of fat in men tends to be around their abdomens, resulting in an ‘apple shape.’13

Measuring body fat is difficult to do directly. As a result, Body Mass Index, (BMI) a measure of weight in relation to height, is often used. Other forms of measurement can include waist circumference, hip circumference, waist-hip ratio and percentage of body fat. See Chapter Two for more information. (link to chapter 2)

The WCRF/AICR Report presents its findings related to the strength of the evidence found in the research reviewed by the expert panel. This process of Judging the Evidence is a comprehensive and meticulous process which can result in a recommendation if the evidence is strong enough, or can result in the need for more research if the evidence is lacking. Findings are categorized using the following grading criteria:14

- “Strong evidence…support(s) a judgement of a convincing or probable causal (or protective) relationship and generally justify making public health recommendations.”

- “Convincing evidence…support(s) a judgement of a convincing causal (or protective) relationship which justifies making recommendations designed to reduce the risk of cancer… (and) robust enough to be unlikely to be modified in the foreseeable future.”

- “Probable evidence…support(s) a judgement of a probable causal (or protective) relationship, which generally justifies goals and recommendations designed to reduce the risk of cancer.”

- “Limited evidence…is inadequate to support a probable or convincing causal (or protective) relationship.”

- “Limited – suggestive evidence is inadequate to permit a judgement of a probable or convincing causal (or protective) relationship, but is suggestive of a direction of effect…(and) generally does not justify making recommendations.”

- “Limited – no conclusion (indicates) there is enough evidence to warrant Panel consideration, but it is so limited that no conclusion can be made.”

- “Substantial effect on risk unlikely (indicates) evidence is strong enough to support a judgement that a particular lifestyle factor relating to diet, nutrition, body fatness or physical activity is unlikely to have a substantial causal (or protective) relation to a cancer outcome.”

Judgements made in the Report regarding body fatness and weight gain and the risk of development of specific cancer types are found in Table 1.

Table 1: Body fatness and weight gain and the risk of cancer13

|

BODY FATNESS AND WEIGHT GAIN AND THE RISK OF CANCER |

|||||

|

WCRF/AICR GRADING |

DECREASES RISK |

INCREASES RISK |

|||

|

Exposure |

Cancer site |

Exposure |

Cancer site |

||

|

STRONG EVIDENCE |

Convincing |

|

|

Adult body fatness |

Oesophagus (adenocarcinoma) 20161 Pancreas 20121 Liver 20152 Colorectum 20171 Breast (postmenopause) 20171,3 Endometrium 20134,5 Kidney 20151

|

|

Adult weight gain |

Breast (postmenopause) 20173 |

||||

|

Probable |

Adult body fatness |

Breast (premenopause) 20171,3 |

Adult body fatness |

Mouth, pharynx and larynx 20181 Stomach (cardia) 20162 Gallbladder 20152,7 Ovary 20142,5,8 Prostate 20141,9 |

|

|

Body fatness in young adulthood |

Breast (premenopause) 20173,6 Breast (postmenopause) 20173,6 |

||||

|

LIMITED EVIDENCE |

Limited – suggestive |

|

|

Adult body fatness |

Cervix (BMI> 29kg/m2) 20172,5 |

|

STRONG EVIDENCE |

Substantial effect on risk unlikely |

None identified |

|||

|

|||||

World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity: Body fatness and weight gain and the risk of cancer. https://www.wcrf.org/diet-activity-and-cancer/global-cancer-update-programme/resources-and-toolkits/#accordion-1.

WCRF/AICR Diet, Nutrition and Physical Activity Recommendations for the Prevention of Cancer

From the Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: a Global Perspective 2018 there are ten diet, nutrition and physical activity recommendations presented which will be reviewed in this section. Recommendations are meant to advise all individuals, families, health professionals, communities and policy makers on ways in which to adopt healthy living habits that can work towards decreasing cancer risk. The Recommendations are very practical, including goals and focusing on specific foods and beverages rather than on individual nutrients. They are meant to be thought of as a whole, with the goal for the Recommendations to be “adopted as a lifestyle package,” with all of the Recommendations working together and not in isolation.15

The Report also includes matrices of summaries of both a Summary of Conclusions of the Report and more specifically, a Summary of Strong Evidence from the Report.

WCRF/AICR Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer Prevention Recommendations15

- Be a Healthy Weight

This first recommendation encourages weight to be kept within a healthy range throughout life and avoiding weight gain as an adult. This includes ensuring that a healthy weight is maintained during childhood and adolescence. Weight maintenance may be one of the most important things we can do to protect ourselves from cancer. Because of current trends towards decreased activity and increased overweight and obesity, if these trends remain unchanged, overweight and obesity are expected to surpass smoking as the primary risk factors for cancer.

More specifically, this recommendation presents strong evidence that links being overweight with certain types of cancers. These include cancers of the esophagus, pancreas, liver, colon, kidney, lining of the uterus or endometrium, and breast cancer in women after menopause.

Goals include working towards maintaining a Body Mass Index (BMI) at the lower end of normal towards and through adulthood. A healthy BMI is 25 kg/m2 or less for most individuals. BMI may not be suitable for athletes, the elderly, pregnant women, or children and adults less than 5 feet tall. Additional goals include avoiding an increase in waist circumference through adulthood. A healthy waist measurement for most adults is less than 31.5” for women and 37” for men.

2. Be Physically Active

This second recommendation encourages us to be both physically active as part of everyday life by following or exceeding national guidelines and limiting sedentary behaviors. The World Health Organization recommendations and Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans advise adults engage in daily moderate intensity activity that adds up to at least 150 minutes each week or at least 75 minutes of vigorous physical activity weekly. Children and adolescents ages 6-17 should accumulate 60 minutes or more of physical activity every day with most activities being either moderate- or vigorous-intensity physical activity.

For cancer prevention, it is suspected that the greater amount of physical activity, the greater the benefit. Physical activity should be a part of everyday life by walking more and sitting less, working towards an accumulation of daily activities that add up to the weekly goals. The weekly goals include accumulating 150 minutes of moderate intensity activities or 75 minutes of vigorous activities each week. Besides walking, activities that are considered moderate intensity are the kind that gets your heart beating a bit faster and makes you breathe more deeply. They include cycling, household chores, gardening, swimming and even dancing. Vigorous activities include those that raise your heart rate and cause you to sweat and feel out of breath such as running, fast swimming, fast cycling, and aerobics.

Minimizing the time spent being sedentary is also strongly recommended. This is especially important for adults who have occupations that require long periods of sitting. Making sure to move throughout each day is very important.

This recommendation was made due to the strong evidence that physical activity helps protect against several types of cancer including colon and breast cancers.

3. Eat a Diet Rich in Whole Grains, Vegetables, Fruit and Beans

This third recommendation, and the next three after it, focus on diet choices. This recommendation encourages making wholegrains, vegetables, fruit, and legumes a major part of the diet. Unprocessed plant foods are rich in nutrients and fiber. If consumed as a main part of the diet in place of primarily processed foods that can be high in fat and refined starches and sugars, these whole plant foods can help to protect against weight gain, overweight and obesity and related cancers.

Research has indicated that vegetables may have many health benefits including a decreased risk of cancer, heart disease and obesity. There are specific recommendations regarding the type of vegetables to focus intake on. Non-starchy vegetables such as carrots, green beans and broccoli, are encouraged most often over starchy vegetable such as potatoes, corn, peas and yams. According to the WCRF/AICR Report, evidence for eating non-starchy vegetables is convincing for a decreased risk of cancers of the head and neck area, which includes the mouth, pharynx, larynx and nasopharynx, as well as of the esophagus, lung, stomach and colorectal area.

Foods, including fruits, with a high fiber content have a probable decreased risk of cancers of the mouth, pharynx, larynx and nasopharynx, as well as of the esophagus, lung, stomach and colorectal area. Possibly due to their high fiber content, whole grains can help with digestion and are thought to contribute to protection against colorectal cancer.

Overall diets high in wholegrains, non-starchy vegetables, fruit and beans are associated with a lower risk of certain types of cancer including that of the colon. These nutrient dense foods also help to prevent weight gain and overweight and obesity, in turn providing overall protection from many cancer types.

4. Limit Consumption of ‘Fast Foods’ and Other Processed Foods High in Fat, Starches or Sugars

The fourth recommendation encourages limiting the consumption of fast foods and processed foods, including many prepared or convenience foods, snacks, bakery foods, desserts and candy. Some popular snacking foods that are high in fat and calories, such as nuts and seeds, can be important sources of nutrients and a good choice if eaten in moderation.

Fat and calorie dense foods can contribute to weight gain and associated cancers as well as other chronic diseases. They can also raise blood sugar and insulin levels which can promote an increase in the risk of cancer in the lining of the uterus or endometrium.

5. Limit Consumption of Red and Processed Meat

This recommendation has been included by the WCRF/AICR Panel due to strong evidence that consuming red meat and processed meat are causes of colorectal cancer. More specifically, the recommendation encourages those who eat red meat including beef, pork and lamb, to limit it to no more than three lean portions equal to a total of 15-18 oz (cooked weight) each week and to have little, if any, processed meat. Processed meats are encouraged to be saved for special occasions only, if at all. Examples of processed meats are bacon, bologna, salami, hot dogs, sausages and ham. These meats are usually preserved by smoking, curing or salting or by the addition of preservatives. When meat undergoes this processing, cancer causing substances can be formed which in turn can lead to cell damage and the development of cancer. It is uncertain at this time what exactly about processed meats is cancer promoting.

Certain cancer-causing substances are formed on protein foods during grilling and other high heat cooking methods such as pan frying and broiling. Some of these substances are produced in “muscle meats” including red meat, poultry, game and fish during high heat cooking methods. Others are formed when the fat drips onto the hot stones or coals of the grill, accumulating onto the food when smoke and flare-ups occur. According to the AICR, cooking meats at high temperatures can cause two types of cancer-causing substances to form on or in the meat: 1) heterocyclic amines or HCAs; and 2) polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons or PAHs. Charring and cooking meat, poultry and fish at high temperatures can lead to the formation of HCAs. PAHs typically get into the meat through the smoke that occurs while cooking on the grill. Research on these substances has shown that HCAs and PAHs can cause changes in DNA that may increase the risk of cancer.16

6. Limit Consumption of Sugar Sweetened Drinks

Limiting sugar sweetened drinks and drinking mostly water and other unsweetened drinks such as tea or coffee are encouraged in this sixth recommendation.

Examples of sugar sweetened drinks include soda, energy drinks, sports drinks, bottled teas and coffee drinks with added sugar. These beverages are high in sugar thus calorie-, not nutrient-, dense, and don’t promote feelings of satiety even when consumed in large quantities. Researchers have found that our brains tend to register intake from liquids differently than solids. As a result, they have been found to be a cause of weight gain, overweight and obesity in both children and adults.

7. Limit Alcohol Consumption

For cancer prevention, it is best to limit alcohol consumption.

Alcohol is a cause of several types of cancer including cancers of the mouth and esophagus, liver, and breast in postmenopausal women. Water is the recommended beverage of choice. For those who choose to drink alcohol, the Dietary Guidelines state the following: limit intake to 2 drinks per day for men and 1 drink per day for women, A drink is generally defined as 12 ounces of beer, 5 ounces of wine or 1.5 ounces of 80 proof distilled spirits.17

Many choices you make to lower the risk of cancer also lower the risk of heart disease. But trying to make a smart choice about alcohol can be confusing because alcohol, especially red wine, has been promoted as a heart-healthy choice. Unfortunately, as previously stated, alcohol also presents a cancer risk. There is particular concern regarding the risk for women and breast cancer. The risk starts at relatively low amounts of alcohol intake. According to AICR, “Just 10 grams of pure alcohol consumed daily raises the risk of premenopausal breast cancer 5 percent, and the risk of postmenopausal breast cancer 9 percent.”18

As a result, there are differences in opinion on how alcohol affects the risk of heart disease and cancer, but there is agreement about following guidelines that encourage moderation. Guidelines for heart health emphasize that alcohol, such as red wine, should not be consumed specifically for a potential cardiovascular benefit.19

8. Do Not Use Supplements for Cancer Prevention

This recommendation is derived from studies that have shown that high-dose supplementation has not consistently shown protection against cancer and may be detrimental. For example, some years ago, high dose beta carotene supplementation was shown to cause lung cancer in smokers.20

There have been some studies showing benefit from the use of supplements such as taking calcium for protection against colorectal cancer,21 but primarily, benefits of nutrients and cancer prevention are demonstrated when the nutrients come from food.

This does not refer to the taking of supplements when they are recommended or ordered by a qualified health professional. For example, taking adequate calcium and vitamin D to promote bone health, taking iron for anemia or expectant mothers taking prenatal vitamins is a different matter. This recommendation is specifically to not use supplements as a way to prevent cancer and to meet nutritional needs primarily through diet.

9. For Mothers: Breastfeed Your Baby, if You Can

In addition to the many benefits of breastfeeding, including protecting the infant against infections and childhood diseases, there is strong evidence that breastfeeding protects the mother against breast cancer. In addition to this, a child who is breastfed is protected against later excess weight gain, overweight and obesity throughout childhood. This is important as excess weight gain in childhood often continues into adulthood.

10. After a Cancer Diagnosis: Follow Recommendations, if You Can

The tenth recommendation is for cancer survivors.

Cancer survivors should always check with their physician regarding diet, nutrition and physical activity, but the overall recommendation that has been made by the Expert Panel is that after a cancer diagnosis, cancer survivors should follow the other Recommendations as is possible after the acute stage of their treatment is over.

Each cancer survivor is unique, and their circumstances are all vastly different, but it is recognized that diet, nutrition and physical activity are an important part of recovery and in overall cancer survival. For example, for breast cancer survivors, there is some evidence that factors such as weight and physical activity levels may influence outcomes. The evidence for this is limited at this time and more studies are needed.

In addition, because more people are surviving cancer than ever before, following these cancer prevention recommendations may help to improve their survival and reduce their risk of another cancer diagnosis or the diagnosis of another chronic disease.

The WCRF/AICR Report also emphasizes the importance of avoiding other cancer-promoting lifestyle behaviors including smoking, exposure to tobacco and exposure to excess sun.

American Cancer Society Guideline for Diet and Physical Activity for Cancer Prevention22

The American Cancer Society (ACS) is another organization that works towards supporting and educating the public regarding cancer and cancer prevention. The ACS Guideline for Diet and Physical Activity for Cancer Prevention was developed in 2020 by national experts in the field of cancer and has aligned its recommendations within the Guideline with the WCRF/AICR recommendations, the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans23 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Healthy Choices cancer prevention guidance24.

There are four recommendations within the ACS Guideline and additional recommendations that address the need for community action to coincide with the recommendations for individuals.

Recommendations for Individual Choices22

- Achieve and Maintain a Healthy Body Weight Throughout Life

This first ACS recommendation encourages individuals to keep their weight within a healthy range and to avoid weight gain as an adult. The recommendation cites dietary factors that are known to lead to excess body fat, namely sugar sweetened beverages, “fast foods” and other foods within a “Western” dietary pattern. Rather, individuals should aim to follow a “Mediterranean” dietary pattern that may reduce cancer risk.

2. Be Physically Active

This recommendation encourages all Americans, children through adults, to move more and sit less by limiting sedentary behaviors such as sitting, lying down, and engaging in screen-based entertainment. Recommended amounts of movement are 150-300 minutes of moderate-intensity physical activity weekly or 75-150 minutes of vigorous-intensity activity weekly for adults, and at least one hour of moderate- or vigorous-intensity activity each day for children.

3. Follow a Healthy Eating Pattern at All Ages

This ACS recommendation includes the following specifics regarding a healthy eating pattern:

A healthy eating pattern includes:

- Foods that are high in nutrients in amounts that help achieve and maintain a healthy body weight;

- A variety of vegetables – dark green, red and orange, fiber-rich legumes (beans and peas), and others;

- Fruits, especially whole fruits with a variety of colors; and

- Whole grains.

A healthy eating pattern limits or does not include:

- Red and processed meats;

- Sugar sweetened beverages; or

- Highly processed foods and refined grain products.

In addition to the above, this recommendation also presents similar information as in the WCRF/AICR recommendations regarding the use of dietary supplements stressing that although there is evidence that plant-based foods may reduce cancer risk, there is “limited and inconsistent” evidence regarding the use of supplements to reduce cancer risk.

5. It is Best Not to Drink Alcohol

This recommendation again echoes that of the WCRF/AICR Report in stressing the positive relationship between alcohol intake and the risk for developing cancer as well as other noncommunicable diseases.

For individuals who choose to drink alcohol, they should limit their intake to no more than one drink per day for women and two drinks per day for men.

Recommendations for Community Action22

The ACS Guideline includes information regarding the fact that some individuals may be unable to follow their four recommendations due to circumstances beyond their control. For example, the cost of affordable healthy foods and limited access to healthy choices is an issue for some as is the ability to engage in physical activity.

As a result, the ACS Recommendation for Community Action is as follows:

“Public, private and community organizations should work collaboratively at national, state, and local levels to develop, advocate for, and implement policy and environmental changes that increase access to affordable, nutritious food; provide safe, enjoyable, and accessible opportunities for physical; and limit access to alcoholic beverages for all individuals.”22

To achieve the above Recommendation in communities, the following are also recommended:

- Improving Healthy Eating and Active Living-Related Environments

- Increasing Access to Healthy, Affordable Foods

- Increasing Access to Opportunities for Physical Activity, Play, Leisure Time Activity, and Transportation

- Decreasing Access to Alcoholic Beverages

Finally, the ACS Guideline also recommends healthcare involvement by developing and implementing Clinical Strategies to Promote Healthy Eating and Active Living and Limiting Alcohol. Those in a position to create change in policies, are encouraged to endorse Public Policy Approaches to Promote Healthy Eating and Active Living.

Summary

There is a long history of those in the medical profession contemplating and researching the potential links between nutrition, physical activity and cancer. In more recent years, this research has grown dramatically, yielding extensive results that have been interpreted by current experts in the field and culminating in practical cancer prevention guidelines. One of many important findings include the link between energy balance, body fatness and the risk of cancer. With the growing worldwide obesity statistics, in children through adults, this information is both timely and instructive. As a result, both the WCRF/AICR Diet, Nutrition and Physical Activity and Cancer Prevention Recommendations and the Recommendations for Individual Choices within the ACS Guideline for Diet and Physical Activity for Cancer Prevention have chosen weight management as their primary recommendation, followed by the promotion of increased physical activity and decreased sedentary behaviors. Diet recommendations follow this theme, with recommendations to limit energy-dense foods and beverages such as bakery food, desserts, candy and sugar sweetened drinks as well as to avoid alcoholic beverages. All diet-related recommendations lean towards a plant-based, nutrient-dense diet that is low in processed foods, including processed meats. Both the WCRF/AICR Report and the ACS Guideline provide an excellent framework for promoting their recommendations in clinical and community settings.

Resources

American Institute for Cancer Research

ACS Guideline for Diet and Physical Activity for Cancer Prevention

NIH-National Cancer Institute, Cancer Prevention Overview (PDQ®)

References

- Kiple KF, Ornelas KC. The Cambridge World History of Food. Cambridge University Press. Cambridge, UK. 2000.

- Schatzkin, A. Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics. National Cancer Institute, 2005.

- Dishman RK, Washburn RA, Heath GW. Physical Activity Epidemiology, 2004.

- Jurdana M. Physical activity and cancer risk. Actual knowledge and possible biological mechanisms. Radiol Oncol. 2021;55(1):7-17. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7877262/

- National Institutes of Health. National Cancer Institute. What is cancer? Accessed December 2022. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/understanding/what-is-cancer.

- National Institutes of Health. National Cancer Institute. What is cancer? Accessed December 2022. https://www.cancer.gov/types/common-cancers.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancer data and statistics. Accessed December 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/data/.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancer statistics at a glance. Accessed December 2022. https://gis.cdc.gov/Cancer/USCS/#/AtAGlance/.

- National Cancer Institute and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State cancer profiles. Quick profiles: New Jersey. Accessed December 2022. https://statecancerprofiles.cancer.gov/quick-profiles/index.php?statename=newjersey.

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: A Global Perspective. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018.

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: A Global Perspective. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. A summary of the third expert report. Accessed December 2022. https://www.wcrf.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Summary-of-Third-Expert-Report-2018.pdf.

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity: Energy balance and body fatness. Accessed December 2022. https://www.wcrf.org/diet-activity-and-cancer/global-cancer-update-programme/resources-and-toolkits/#accordion-1.

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity: Body fatness and weight gain and the risk of cancer. Accessed December 2022. https://www.wcrf.org/diet-activity-and-cancer/global-cancer-update-programme/resources-and-toolkits/#accordion-1.

- World Cancer Research Fund International. Judging the evidence. Accessed December 2022. https://www.wcrf.org/diet-activity-and-cancer/global-cancer-update-programme/judging-the-evidence/.

- World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research. Diet, Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer: A Global Perspective. Continuous Update Project Expert Report 2018. Recommendations and public health and policy implications. Accessed December 2022. https://www.wcrf.org/diet-activity-and-cancer/global-cancer-update-programme/resources-and-toolkits/#accordion-1.

- American Institute for Cancer Research. Cancer researchers issue yearly warning on safer grilling. Accessed December 2022. https://www.aicr.org/news/cancer-researchers-issue-yearly-warning-on-safer-grilling/.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 9th Edition. 2020. Accessed December 2022. DietaryGuidelines.gov.

- American Institute for Cancer Research. Mixed messaging on red wine: separating myth from fact. Accessed December 2022. https://www.aicr.org/resources/blog/mixed-messaging-on-red-wine-separating-myth-from-fact/.

- American Heart Association. Drinking red wine for heart health? Read this before you toast. Accessed December 2022. https://www.heart.org/en/news/2019/05/24/drinking-red-wine-for-heart-health-read-this-before-you-toast.

- Goralczyk R. Beta-carotene and lung cancer in smokers: review of hypotheses and status of research. Nutr Cancer. 2009;61(6):767-74. doi: 10.1080/01635580903285155. PMID: 20155614.

- Bonovas S, Fiorino G, Lytras T, Malesci A, Danese S. Calcium supplementation for the prevention of colorectal adenomas: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Gastroenterol. 2016 May 14;22(18):4594-603. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v22.i18.4594. PMID: 27182169; PMCID: PMC4858641.

- Rock CL, Thomson C, Gansler T, Gapstur SM, McCullough CL, Patel AV, et. al. American Cancer Society guideline for diet and physical activity for cancer prevention. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:245-271.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans, 2nd edition. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. Accessed December 2022. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancer: healthy choices. Accessed December 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/prevention/other.htm.