5 Chapter Five: Physical Activity Interventions for Obesity Prevention

Authored by Christine Zellers, MPP

Chapter Outline

Sedentary Lifestyle Implications and Physical Activity Recommendations

What is Physical Activity?

Recommendations for Physical Activity

Implications of American’s Physical Inactivity Geographically, Ethnically and Racially

Types of Physical Activity

Aerobic/Cardiovascular

Muscle Strengthening

Bone Strengthening

Balance Flexibility

Measurements of Physical Activity Rates

Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET)

Examples of Moderate and Vigorous Physical Activities

Heart Rate Estimating Heart Rate Other Exertion Indicators Trends and Safety

Physical Activity for Improved Health Outcomes and Chronic Disease Prevention

Obesity

Chronic Disease Prevention and Implications of Expanded Mortality

Improved Overall Health Outcomes/Longevity of Life – Metabolic Health

Benefits vs Risk of physical activity

Benefits

Risks

Behavioral Strategies for Physical Activity and its Impact on Disease Prevention

Policy, Systems and Environmental Change for Physical Activity

Policy

Systems

Environmental

Policy Systems and Environmental Change for Creating Equitable Health Outcomes

Implications and Outcomes of Built Environments

Physical Activity Community Interventions

Summary – Public Health Implications of Physical Activity

Resources

Critical Thinking Questions

References

Sedentary Lifestyle Implications and Physical Activity Recommendations

Physical activity has positive health implications for chronic disease prevention in the United States, yet Americans fall short of recommended amounts of movement. A sedentary lifestyle is inactive behavior where a person tends to spend most waking hours in a sitting or lying position and not moving regularly throughout the day. Technological advances, less manual labor, and easy access to basic human survival essentials like food and water coupled with urbanization and changing transportation patterns have decreased the amounts and types of physical activity Americans participate in daily. The World Health Organization (WHO) notes that worldwide, 1 in 4 adults and 3 in 4 adolescents (ages 11-17) do not currently meet the global recommendations for physical activity.1 Sedentary lifestyles are associated with 117 billion dollars annually in healthcare costs and are the reported cause of 1 in 10 premature deaths according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States.2 Scientific evidence associates physical activity with chronic disease prevention making promotion of physical activity a critical component of community health interventions.

What is Physical Activity?

It is important to note that while both exercise and physical activity can be used somewhat interchangeably, the broad definition that both encompass are not exclusively right or wrong in defining movement. When used to encourage a less sedentary lifestyle both are beneficial definitions of movement. Exercise is defined by the CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) and the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (PAGA) as, “a type of physical activity that involves planned, structured, and repetitive bodily movement done to maintain or improve one or more components of physical fitness.”3 Physical activity is defined by the CDC’s NCHS as “any bodily movement that is produced by the contraction of skeletal muscle and that substantially increases energy expenditure.”3 Use of the phrase physical activity in place of exercise is being promoted by the United States Department of Health and Human Services through the Move Your Way Campaign. This campaign seeks to encourage Americans to move more within the limits of their everyday lives rather than being stringent in an exercise routine.4 Messaging from this campaign is focused on movement in any form or duration to incorporate movement into personal daily routines versus exercise which must be in addition to regular movement and at a scheduled time. This campaign aims to take the stigma from exercise to get Americans to be more physically active.

Recommendations for Physical Activity

The PAGA 2018 is produced by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services through rigorous review and contributions from researchers and available scientific literature.5 These guidelines are designed for health professionals and policy makers to use as guidance for program implementation and policy development. The first and overarching recommendation of the PAGA is to move more and sit less. The guidelines also establish types, amounts, and intensity levels for physical activity while providing suggestions for policies that make physical activity accessible to all Americans.

Physical activity is divided into two categories, aerobic or cardiovascular exercise and muscle strengthening exercises. Bone strengthening, flexibility and balance movements are important for both chronic disease prevention and healthy aging. These three activities often fall within the two main groups of exercise. For example, running is an aerobic exercise that is also bone strengthening and yoga is a flexibility activity as well as muscle strengthening.

General recommendations for adult physical activity are 150 to 300 minutes minimum of aerobic exercise each week and an additional two days that include weight bearing exercise.5 Recommendations are spanned over the week to provide ample opportunities for adults to meet the minimum requirements rather than being grouped by day.

Recommendations for children are a minimum of 60 minutes of movement per day. Children and adolescents (ages 6-17) should engage in 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous exercise daily to support healthy growth and prevent obesity.5 Youth should include aerobic activity, muscle-strengthening, and bone-strengthening activities as part of the 60 minutes of daily activity (see table 1) Children should include a mixture of all three types of movement at least three days per week each. Children under the age of 3 should engage in regular play throughout the day to provide ample movement. It is recommended that preschool aged children (ages 3-5) be physically active with a variety of activities throughout the day to support growth and development. It is important that children engage in a variety of age-appropriate movement that stimulates and supports interests to encourage movement throughout the life span.

Guidelines are further categorized by special groups such as women during pregnancy and postpartum period, adults with chronic health conditions and adults with disabilities. During pregnancy and the postpartum period women should engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate intensity aerobic activity per week, spread throughout the week. Those women who engaged in vigorous-intensity aerobic activity or who were physically active before pregnancy can continue those activities during pregnancy and the postpartum period. These recommendations should be discussed with a physician who is overseeing the pregnancy and postpartum period to properly adjust activity levels as needed. Adults with chronic conditions or disabilities should participate in regular physical activity and recommendations are the same for this special group as those with no health-related conditions however, a physician should be consulted regarding the types and amounts of activity appropriate for specific individuals. Adults with chronic conditions or disabilities unable to meet the key guidelines should engage in regular physical activity according to their abilities and avoid physical inactivity. Older adults should follow the same recommendations as other adults within personal limits and fitness levels and include balance training along with aerobic and muscle-strengthening activities. 5

Table 1. Examples of type and amounts of physical activities for youth ages 6-17

|

Type of Physical Activity |

Recommended Amounts |

Examples* |

| Aerobic | 3 times per week as part of 60 minutes/day | Swimming, running, biking, dancing |

| Muscle-strengthening | 3 times per week as part of 60 minutes/day | Body resistance like push-ups,

weightlifting, resistance bands |

| Bone-strengthening | 3 times per week as part of 60 minutes/day | Running, jumping rope, basketball |

Adapted from Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans 2nd edition

to demonstrate examples of physical activity and duration for youth.

*Some examples may fit into more than one type of physical activity.

The Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans 2nd Edition (2018) was created by the United States Department of Health and Human Services and serves as a resource for professionals to educate the public on physical activity guidelines.

Implications of American’s Physical Inactivity Geographically, Ethnically and Racially

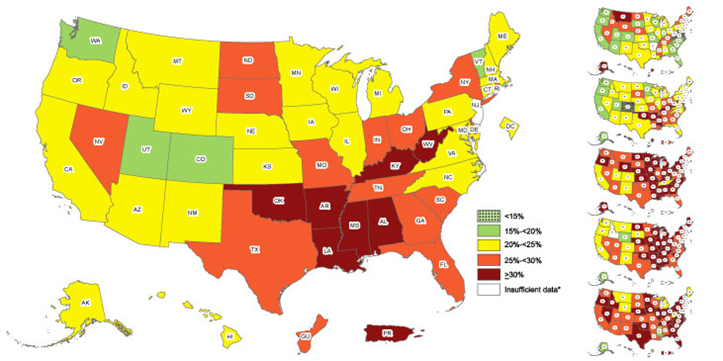

Current rates of inactivity have strong implications across the country both geographically, racially, and ethnically and serve as a marker for health inequities (see Figure 1) In 2022 the CDC created maps to demonstrate physical activity trends that were compiled in three separate sub-sections of race, ethnicity, and geographic area using data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS).6 These maps which used a marker of physical inactivity for adults, defined as a lack of participation in any leisure-time physical activities over a one-month period, concluded that there was a variable range between 17.3% and 47.7% of the adult population who were physically inactive. 6 BRFSS collected data for these maps using telephone surveys and concluded physical inactivity is most prevalent in Hispanic adults (32.1%), non-Hispanic Black (30%), non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native (29.1%) non-Hispanic White (23%) and non-Hispanic Asian adults (20.1%).6 Ethnic and racial statistical data on inactivity indicated higher prevalence of inactivity among specific groups may be precipitated by lack of accessibility to safe exercise options. Additionally, geographic results divided by states and territories concluded variable levels of physical inactivity across racial and ethnic groups whereby demonstrating states and territories that had greater levels of inactivity demographically. Finally, location specific data was collected to identify areas of the United States with the greatest levels of inactivity indicating Colorado had only 17% of residents who were inactive outside of work responsibilities and Puerto Rico recording the highest prevalence of physical inactivity at 49.4%. Location is divided further into geographic region with the south (27.5%) showing the most physical activity, Midwest (25.2%), Northeast (24.7%) and West (21.0%). In totality these data sets demonstrate the need for a reduction to barriers of physical activity where Americans work, live, and play.

Figure 1. Differences in the prevalence of physical inactivity in the United States exists by race/ethnicity and location according to CDC Maps (2022).6

Types of Physical Activity

Physical activity recommendations are grouped into two specific types, aerobic or cardiovascular and muscle strengthening. Both aerobic and strengthening exercises provide varied but equally important contributions for reducing inactivity and preventing chronic disease. Physical activity terms such as intensity levels, frequency, duration, sets, and repetition are used to establish a range to measure how hard the body is working or for how long. Additionally, other important measurements of intensity levels include heart rate, exertion levels and metabolic equivalent of task (MET). Just as it is important to eat a variety of nutrient dense foods so is incorporating a variety of physical activities to support overall health across the lifespan.

Aerobic/Cardiovascular

Aerobic physical activity also referred to as cardiovascular, or cardio is the movement of large muscle groups in the body over a sustained period in a systematic rhythm.5 Examples of aerobic physical activity include brisk walking, running, bicycling, or swimming. It is an activity that causes increased heart rate and breathing. Aerobic activity is divided into three components according to the PAGA, intensity level, frequency, and duration. 5 Intensity refers to how hard a person is working during the aerobic exercise while frequency is how often the activity occurs and duration is how long someone moves in a single session. While all three of these components represent a measure for aerobic movement, for purposes of the public, aerobic activity is recommended in total weekly movement of 150-300 minutes of aerobic physical activity.

Muscle Strengthening

Muscle strengthening activities include resistance training and weightlifting and are used to build muscle in the body for strengthening the various muscle groups. Activities that are considered muscle strengthening include weightlifting, resistance band exercises, or weight bearing exercises like push-ups. The repetitive nature of muscle strengthening coupled with lifting objects heavier than everyday activities assists with increasing muscle strength.

Similar to aerobic exercise, there are three identifiable components of muscle strengthening – intensity, frequency and sets or repetitions. Intensity is used to determine the amount of weight or how heavy the force is; frequency is how often a person engages in muscle strengthening activities; and sets or repetitions refers to how many times a person does the movement; for instance, 3 sets of 10 push-ups 5 Recommendations for muscle strengthening include participating in this physical movement at least 2 times per week and making sure to work all major muscle groups. The major muscle groups include abdomen, arms, back, chest, hips, legs, and shoulders. Opposing muscles should be developed for equal strength and to prevent injury from one muscle being stronger than the opposing muscle.

Bone Strengthening

No specific recommendations are given for amounts of bone strengthening activities in the Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans however these movements help prevent bone related diseases and promote overall strength and growth. Bone strengthening activities include impact movements and weight-bearing exercises such as running, brisk walking and weightlifting, these activities can be included in either the aerobic or muscle strengthening physical activity categories.

Balance

Incorporating balance activities becomes increasingly important as we age as well as throughout the lifespan. Balance activities prevent falls and can be completed by balancing on one leg, walking backwards, or standing from a seated position by engaging core muscles and not using one’s hands to stabilize during the movement. Balance movements are supported by a strong core or abdomen and back, and strong legs to assist with everyday activities. 5Poor balance is associated with falls in older adults therefore establishing good balance can aid in fall prevention and the ability to live independently. Much like bone-strengthening activities balance does not have a set amount of recommended time, however, better balance can improve movement in everyday life.

Flexibility

Much like good balance, flexibility is critical for increasing the capability to be more physically active and preventing injury or falls. There are not any specific guidelines for the amount of flexibility exercises, however activities such as stretching, yoga and tai chi can increase flexibility and support joints to enable full range of motion with all body parts.

Measurements of Physical Activity Rates

Moderate and vigorous are physical activity terms that broadly describe the intensity level of physical activity, however other measurements such as heart rate and Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET) are also indicators of energy expenditure that can be more accurate than a personal perceived rate of exercitation. Metabolic Equivalent of Task or MET describes the energy level expenditure in a specific physical activity.5 While METs give a range for energy burned and intensity level, heart rate echelons provide a personal measurement of heart exertion levels during physical activity. Both METs and heart rate measurements will vary depending on a person’s age, gender, and physical fitness level. Both can be used as indicators but neither creates a perfect means of measuring activity intensity levels. While participating in any type of movement is better than no movement at all, the intensity, duration, and frequency can increase energy expenditure as these components increase. For people who already participate in regular activity, knowing how to measure these areas of energy expenditure may assist with creating better endurance and fitness levels.

Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET)

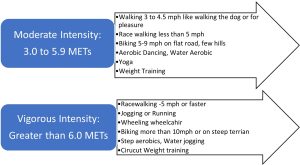

Metabolic Equivalent of Task (MET) are scaled depending on the amount of energy being expended to complete a task. METs are scaled using 1 as a resting level then increasing depending upon the level of energy expenditure. Moderate physical activity might expend 3.0-5.9 METs and vigorous exertion is considered 6.0 or more METs. 5 A MET score of over 8 is high intensity.5 (see Figure 2) While METs give a range for energy burned and intensity level, heart rate echelons provide a personal measurement of heart exertion levels during physical activity and can assist with indicating MET levels.

Figure 2. Examples of Moderate and Vigorous Physical Activities

Adapted from the CDC’s General Physical Activities Defined by Level of Intensity5,7

Heart Rate

Exercise amounts, heart rate and exertion levels all contribute to the benefits of physical activity. Heart rate is measured by the number of times the heart beats during an activity or at rest. Resting heart rates can indicate a person’s overall fitness level, higher fitness levels do not require the heart to work as hard because it is more efficient which creates a lower resting heart rate and better fitness level. Higher resting heart rates indicate the heart is working harder to pump blood through the body and isn’t as efficient or physically fit. Target heart rate provides a guidance for exertion levels, but it is not a perfect science for determining intensity levels. By first determining the target heart rate for an activity an individual can regulate exertion levels at or below the target heart rate. Heart rate percentages indicate how difficult an activity is for the persons fitness level, age, and gender.

Estimating Heart Rate

Each person’s exertion level will vary depending on their age, weight, and fitness levels. To find your heart rate, stop moving and take your pulse at your neck, wrist, or chest by counting the number of heart beats in a minute. To determine your estimated maximum age-related heart rate, subtract your age from 220.

For example, the formula for a 40-year-old would be:

|

220 – 40 = 180 beats per minute (bpm) |

To determine moderate intensity, the target heart rate should be 64%-75% of maximum heart rate. To estimate moderate exercise rates, use the formula: estimated maximum age-related heart rate x 0.64 = moderate exercise or for a 40-year-old:

|

180 x 0.64 =115 beats per minute for 64% exertion |

For vigorous physical activity levels, the heart rate should be between 77%-93% of estimated maximum age-related and estimating this can be done by using estimated maximum age-related heart rate:

|

Age-related heart rate x 0.77 (to 0.93) = vigorous exercise heart rate |

Other Exertion Indicators

Wearable devices and talk tests are also used to estimate moderate and vigorous levels of movement. Similar to METs and heart rate these devices are useful but may not be an exact method for establishing exertion to the novice exerciser. Wearable devices sometimes called trackers have grown in popularity and like the Move Your Way Campaign were designed to increase activity levels. High level athletes often use wearable devices to determine practice levels and to encourage optimal performance. Devices used for elite athletes, much like those used by everyday novices, record and display information that includes heart rate, minutes of activity, minutes of vigorous activity or zone minutes, calories burnt, sleep activity and steps/miles taken in each period. Talk tests are a free and very subjective way to determine activity levels. According to the CDC if someone can talk but not sing the activity is moderate intensity, and vigorous intensity exercise means a person is unable to speak more than a few words without pausing to take a breath.8

Trends and Safety

The trend to move more and sit less has been met with opposition. To combat this continued sedentary lifestyle of Americans, the guidelines and marketing for physical activity are now being promoted to be less demanding and more inclusive through the Move Your Way campaign. The Move Your Way campaign from the US Department of Health and Human Services supports American’s finding movement in varying increments and appealing methods for busy lifestyles. The program provides support materials and suggestions for enactment by not-for-profit agencies, educational institutions and others who might implement ideas for incorporating movement where and as often as possible. The campaign attempts to take the demand and stigma of routine exercise regimens and encourage physical activity, at personal physical fitness levels and within the time restraints of daily living.4

Safety during physical activity pertains to safe movement and a safe environment. Physical activity is safe for almost everyone and its benefits to health far outweigh the risks. Safe physical activity recommendations in the PAGA include topic areas like safe equipment, appropriate movement for fitness level, gradual increase, a safe environment, and being under the care of a physician.5 Of special note in the safe physical activity recommendations is environment. Community interventions for physical activity should ensure a safe environment for movement, especially marginalized communities who may lack safe resources to access exercise opportunities. Consideration of safe exercise environment include green space, parks free from violence and safe sidewalks and bike lanes. Circumstances such as safe access should be considered when health care professionals encourage physical activity so that recommendations are inclusive and equitable.

Physical Activity for Improved Health Outcomes and Chronic Disease Prevention

Obesity

Obesity rates in the United States continue to rise as Americans eat a high energy diet with poor physical activity levels to counteract calorie consumption. Between 2017-2020 the obesity prevalence in the United States was 41.9% according to the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2017–March 2020.9 Americans need to expend more energy to combat high caloric diets and consequently maintain a healthy weight to reduce the incidence of obesity in both adults and children. Physical activity that burns more energy can result in weight loss and the reduction of co-morbidities associated with obesity. As Americans sit more and move less, obesity has become a national epidemic. According to the State of Obesity: Better Policies for a Healthier America 2022 developed by Trust for America’s Health:

- Nationally, 41.9 percent of adults are obese.

- Black adults had the highest level of adult obesity at 49.9 percent.

- Hispanic adults had an obesity rate of 45.6 percent.

- White adults had an obesity rate of 41.4 percent.

- Asian adults had an obesity rate of 16.1 percent.

- Rural parts of the country had higher rates of obesity than urban and suburban areas.10

Chronic Disease Prevention and Implications of Expanded Mortality

Physical activity has been associated with numerous health benefits in addition to healthy weight management. Symptoms of arthritis through joint friendly physical activities like walking or swimming have been shown to reduce symptoms, improve pain associated with arthritis and improve body function and mood.11 Physical activity can improve sleep quantity and quality and improve cognitive and memory functions due to the increased blood flow physical activities create in the body.12,13 It has also been found to reduce the risk of dementia, including Alzheimer’s Disease.13 Increasing daily step counts from 4,000 to 8,000 has been shown to decrease mortality from various chronic diseases.15 Physical activity can improve aerobic function which supports better cardiovascular health and could prevent heart disease and stroke.16 Systolic pressure and a stronger heart muscle from improved blood flow are also positive outcomes from physical activity. High-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol (good) is raised through regular physical activity and low-density lipoprotein (bad) is lowered which balances cholesterol levels.16 Movement assists the body with insulin burning which can improve blood sugar numbers whereby improving or preventing diabetes.14 Lung function is improved through physical activity and there is evidence that movement like walking could improve lung function in adults with asthma for better asthma control.17 Physical activity supports better bone density and muscle mass to stop the effects of bone loss or osteoporosis.18 Updated in the 2nd edition of the PAGA are findings of 6 types of cancer that could be prevented through regular physical activity which include bladder, endometrium, esophagus, kidney, stomach and lung which were added to the already existing list that included breast and colon cancer.14 The increased blood flow and overall euphoric feeling that physical activity can produce can increase energy and stamina for a better mood therefore physicians have started prescribing more physical activity as a preventative medicine intervention.

Improved Overall Health Outcomes/Longevity of Life – Metabolic Health

Metabolic syndrome has been defined in varying ways by different organizations however the common factors are a “high weight circumference, dyslipidemia, hypertension and insulin resistance.”16 According to the World Health Organization (WHO) “unhealthy diets and a lack of physical activity may show up in people as raised blood pressure, increased blood glucose, elevated blood lips and obesity” which are metabolic risk factors that can lead to cardiovascular disease.19 Metabolic syndrome increases a person’s likelihood of death significantly depending on the disease factors but could be prevented or managed if behaviors were modified to reduce risk factors with interventions such as increased physical activity and a nutrient dense diet.

Benefits vs Risk of Physical Activity

American adults are not active enough and as a result suffer from chronic diseases and ailments associated with a sedentary lifestyle, the benefits of physical activity far outweigh the risks. As has been mentioned in this chapter the benefits of physical activity and impact on physical and mental health are numerous. Additionally, there are limited risk factors to physical activity especially after consulting a physician. Regular movement that is sustained for both children and adults will have positive long term health benefits and has the potential to extend the lifespan.

Benefits

While Americans seemly understand the benefits of physical activity such as improved quality of life, chronic disease prevention and a general sense of well-being this awareness does not appear to be enough to increase amounts of movement. As public health professionals it is important to educate the public and promote physical activity, but it is also critical to realize that information alone is not enough for behavior change. Later in this chapter information is provided on policy, systems, and environmental change which are critical components of public education to increase physical activity and adapt the built environment to support all Americans being more active.

Risks

Reasons for physical inactivity vary and typical barriers include lack of time, injury fears, pain while exercising or chronic pain, and lack of enjoyment. In most cases actual risk factors for exercise are limited.20 Both aerobic and muscle strengthening physical activities support disease prevention and better health outcomes. To debunk the excuses for lack of physical activity public health professionals should promote moving in ways that are enjoyable so that it becomes consistent within everyday routines as is exemplified in the Move Your Way Campaign.

Behavioral Strategies for Physical Activity and its Impact on Disease Prevention

Just as fruits and vegetables are prescribed by doctors for better health outcomes so is physical activity and/or exercise. These non-pharmaceutical options are being prescribed to patients to lessen the effects of or prevent chronic disease, improve overall health, and establish proper weight management.21 Likewise, as an alternative or in addition to pharmaceuticals, prescribing doctors often recommend physical therapy. Appointments with a physical therapist help to remedy an injury or pain by teaching exercises and movements to strengthen afflicted body areas for better mobility and health outcomes. Promotion of non-pharmaceutical interventions as a community intervention has potentially positive outcomes in both preventing obesity related chronic disease and encouraging more physical activity.

Policy, Systems and Environmental Change for Physical Activity

Promoting more physical activity should include teaching people to move more by explaining the recommendations for physical activity as well as providing examples on how to be active. While education is a needed and important component for encouraging healthier behaviors, as a standalone it can be ineffective for influencing long term behavior change. Given the likelihood that education has informed people of the needed behavior change does not mean that the change can be easily made. Community health outreach interventions have expanded to include both education and changes in the built environment. Policy, systems and environmental (PSE) initiatives are now recognized as an essential companion to educational efforts for equitable change. PSE changes are defined in various ways depending on the source; however, the basic premise of these changes is to make a healthy option easily available to everyone. PSE changes create more equitable and accessible means for healthy behavior changes, especially when accompanied with science-based education. Teaching the community while synchronously creating PSE for accessible and equitable physical activity better ensures American’s ability to move.

Policy

Policy in the context of PSE is established on various levels of public or private institutions. Policy change is written and officially documented for implementation verses a suggestion or idea.22 A policy change could include “legislative advocacy, fiscal measures, taxation, and regulatory oversight”. 22 For example, in a school district a policy that might be put into place by the board of education could be to extend the length of time for physical education class in all schools. As a policy this would be voted on by the school board and implemented by all schools in the district. Agencies like the CDC provide suggestions on what and how to implement policy changes while individual institutions and agencies also create policies based on budget needs and available resources.23 One of the most notable policy changes in the Unites States have been smoke free policies in public areas.24 These policies, like many, were met with opposition initially but are now so commonplace that many people under the age of 25 in the United States have never been exposed to secondhand smoke while eating in a restaurant. The gradual introduction of smoke free policies has expanded so that implementing new policies prohibiting use of tobacco products in public spaces is more easily introduced and enacted. It is important to recognize that tobacco policies like other health behavior change policies were not always popular or mainstream and have taken decades to readily enact.

Systems

Systems changes are variations in the way something is done to create better health outcomes.22 A systems change may not be officially documented like a policy, but it could be. An example of a systems change might be having a walking meeting at work. This may not be a policy that is written down but if a supervisor encourages meetings to take place while walking it is changing the traditional system of how things are done. While that is a simple example, more complex systems might be a school making certain days of the week riding school bus days

whereby students ride bikes to school verses riding the bus. This systems change could be voluntary and not written down, although it may also be a policy to provide for proper student care. All three PSE components do have a likelihood to overlap but don’t always. Some systems changes can become policies or environmental changes. For example, changing vending machines at an office to contain only healthy food options is systems change. However, policy makers might see a reduction of obesity levels when this systems change is made and in turn a reduction in health care cost whereby encouraging them to make it a policy that only healthy snacks be in the vending machine. Systems changes are sometimes the first step in creating a policy by providing evidence of positive modification worthy of permanent implementation.

Environmental

Environmental changes usually involve larger scale change; however, some can be small in nature too. Environmental change can involve the physical surroundings like creating a safe walking path for physical activity, as well as social and economic outcomes to change accessibility to better health behaviors and outcomes.22 An example of environmental change are healthy corner store initiatives, that create better access to healthy food choices in food desserts or traditionally food insecure areas. Signs that label a park’s inclusive exercise equipment, walking trails or biking trails and safely lit areas for people to be physically active are environmental changes too. Much like systems changes, sometimes the environment is part of a policy change or acts to make a policy change because of its positive effect on the community.

Policy Systems and Environmental Change for Creating Equitable Health Outcomes

To some people access to safe and affordable physical activity may not require a second thought, however for some physical activity is out of reach due to limitations beyond their control. For instance, in some areas safe outdoor play for children is not available, and in others just going for a walk could be hazardous due to neighborhood violence, traffic dense roads or poorly lit walkways. PSE initiatives and community interventions designed by public health professionals, schools and government agencies establish more equitable physical activity opportunities for all Americans. When educating the public on being more physically active and less sedentary it is important to consider the built environment of the audiences. For instance, are there bike lanes for safe biking, are sidewalks well-lit and free of hazards or is there any green space available? An inability to have access to safe affordable physical activity prohibits people of color and minority groups that are already at high risk for chronic disease from being able to exercise. Inequities in physical activity just like biases in health care, food access and safe living prohibit vulnerable populations from moving to prevent diseases and can disproportionately lead to an un-healthy life. While PSE work has been established in various initiatives nationally, it often is implemented in upper-middle class areas where fewer minority groups live, work and play. To create equity for physical activity, PSE change needs to support accessibility through built environments that are safe and practical for all to use. Policy initiatives seeking to improve physical activity levels through a “built environment should address poverty, safety and social cohesion” to provide more active communities.25

Implications and Outcomes of Built Environments

The goal of the CDC is to get 27 million people moving by 2027. The CDC tool kit provides ideas for stakeholders to support this initiative and reduce chronic disease and obesity with more movement.

According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) built environment is the “man-made or modified structures that provide people with living, working and recreational spaces.”26 Built environments are important in the context of physical activity because poor access reduces the likelihood that people will move. People who live in neighborhoods with inadequate access to “quality housing, sidewalks and parks were up to 60% more likely to be obese or overweight.”27 Policy, Systems and Environmental efforts can improve built environments by encouraging and supporting land use for walkability, less car dependent neighborhoods, active transportation options and policies like safe routes to schools and complete streets.10 In the early 2010s the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Center on Society and Health and Virginia Commonwealth University created maps of major cities to demonstrate the disparities that may occur around a large city depending on the exit of the highway, train stop or zip code. These maps demonstrate how the built environment and access to healthy food and healthcare can drastically change life expectancy within a short geographic distance.27 These maps demonstrate health disparities from one train stop to the next, can make the difference between living 75 years and 85 and amplifies the discrepancy in mortality due to inadequate living, working, and playing standards

Physical Activity Community Interventions

Policy, systems, and environmental changes are designed to make healthier choices easy and community interventions on the national, state, and local level support and encourage Americans to be more active. The Complete Streets program is a national initiative implemented by the U.S Department of Transportation. This effort seeks to make streets safer though evaluation and financial support for bike lanes, sidewalks, crosswalks and even landscaping while promoting walking and biking. It also encourages community planning to ensure sustainability of safe accessible streets for years to come within the infrastructure of municipalities.28 States like New Jersey created specific Complete Streets Policy so that future roadways are accessible and safe to residents, demonstrating how national programs can be implemented and structured for state and local use by planning for the future using policy such as complete streets. New Jersey Safe Routes. The Safe Routes to School from the National Center for Safe Routes to School supports infrastructure as it pertains to children safely walking and biking to and from school and is further demonstration of PSE initiatives that support a more physically active community. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program – Education (SNAP-Ed) supports national physical activity interventions that are implemented on the state and local levels in addition to community nutrition interventions. The SNAP-Ed Toolkit encourages agencies who implement the SNAP-Ed grant to develop physical activity interventions that best serve the state and local community while also funding projects that support movement using parks and public spaces.29 Evidence based strategies for community interventions support behavior change for increased physical activity and chronic disease prevention.

State and Local Examples of Community Interventions

The Complete Streets Movement in New Jersey

Local NJ City Complete Street Example and Process

Local NJ Complete Streets Program that improves city access and economy

Summary – Public Health Implications of Physical Activity

Physical inactivity has become a health crisis in the United States as lack of movement and a sedentary lifestyle contribute to incidence of chronic disease and early morbidity. Obesity due to high caloric diets and poor activity habits have combined to make the perfect storm of a public health crisis. The price of inactivity is evident through loss of work, early onset of chronic diseases and increased healthcare costs for treatment of preventable illnesses. Public health professionals can have a direct effect on the reduction of obesity and chronic disease through educational efforts and PSE initiatives that encourages more deliberate and inclusive access to physical activity. People are constantly looking for a quick and easy way to be fit but the simple solution to better health is regular movement accompanied by a nutrient dense diet that is not higher in calories than the expended amount of energy.

As this chapter has demonstrated there are many promotional and educational programs created by the US Department of Health and Human Services, the United States Department of Agricultures, and Trust for America’s Health, as well as other public health agencies. It is critical for physical activity promotion and PSE initiatives to be consistent and produced by reliable evidence-based sources. Reliable information that can positively influence inclusivity so that all Americans have access to reliable, safe, and affordable physical activity is needed to increase movement to recommended levels.

Resources

Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans 2nd edition

School-based Programs to Increase Physical Activity

Rural Health Information Hub PSE Toolkit

Critical Thinking Questions

- Policy, systems, and environmental change interventions create improvements to make the healthy choice the easy choice. For physical activity what policy, systems and environmental changes could be made to create greater access to safe physical activity for at risk populations? How might these PSE interventions be executed to make change?

- Give an example of a systems change at a school that would create more physical activity.

- Give an example of a systems change that could create more accessibility to all physical activity at a business.

- Give an example of an environmental change that a municipality could create safer access to physical activity.

- Using the Adult Physical Inactivity Prevalence Maps https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/data/inactivity-prevalence-maps/index.html discuss how these maps might be used to create a community intervention to decrease the likelihood of obesity in specific groups, and in specific geographic areas? How might this data be used to support funding for community change?

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Let’s be active. More active people for a healthier world. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/272722/9789241514187-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- 2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Why should people be active? Published July 12, 2022. Accessed September 2, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/activepeoplehealthynation/why-should-people-be-active.html

- 3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey: glossary. Published May 10, 2019. Accessed August 18, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/physical_activity/pa_glossary.htm

- 4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Move your way activity planner. Accessed September 10, 2022. https://health.gov/moveyourway/activity-planner

- 5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans – 2nd edition. Published 2018. Accessed September 1, 2022. https://health.gov/sites/default/files/2019-09/Physical_Activity_Guidelines_2nd_edition.pdf

- 6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult physical inactivity prevalence maps by race/ethnicity. Published October 20, 2022. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/data/inactivity-prevalence-maps/index.html

- 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. General physical activities defined by level of intensity. Accessed October 1, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpa/physical/pdf/pa_intensity_table_2_1.pdf

- 8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Target heart rate and estimated maximum heart rate. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/measuring/heartrate.htm

- 9. Stierman B, Afful J, Carroll MD et al. National Center for Health Statistics (U.S.) national health and nutrition examination survey 2017–March 2020 pre-pandemic data files development of files and prevalence estimates for selected health outcomes. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Published Date: 06/14/2021. Accessed October 2, 2022. NHSR No. 158. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/106273

- 10. Trust for America’s Health. State of obesity 2022: Better policies for a healthier America. Published September 27, 2022. Accessed October 21, 2022. https://www.tfah.org/report-details/state-of-obesity-2022/

- 11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical activity for arthritis. Published February 20, 2019. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/basics/physical-activity-overview.html

- 12. Wang F, Boros S. The effect of daily walking exercise on sleep quality in healthy young adults. Sport Sci Health. 2021;17(2):393-401. doi:10.1007/s11332-020-00702-x

- 13. Di Liegro CM, Schiera G, Proia P, Di Liegro I. Physical activity and brain health. Genes (Basel). 2019;10(9):720. Doi:10.3390/genes10090720

- 14. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Top 10 things to know about the second edition of the physical activity guidelines for Americans. (n.d.). Health.gov. Retrieved October 24, 2022. https://health.gov/our-work/nutrition-physical-activity/physical-activity-guidelines/current-guidelines/top-10-things-know

- 15. Saint-Maurice PF, Troiano RP, Bassett DR Jr, et al. Association of daily step count and step intensity with mortality among US adults. JAMA. 2020;323(12):1151-1160. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1382

- 16. Myers J, Kokkinos P, Nyelin E. Physical activity, cardiorespiratory fitness, and the metabolic syndrome. Nutrients. 2019;11(7):1652. doi:10.3390/nu11071652

- 17. Panagiotou M, Koulouris NG, Rovina N. Physical activity: A missing link in asthma care. J Clin Med. 2020;9(3):706. doi:10.3390/jcm9030706

- 18. Pinheiro MB, Oliveira J, Bauman A, Fairhall N, Kwok W, Sherrington C. Evidence on physical activity and osteoporosis prevention for people aged 65+ years: a systematic review to inform the WHO guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2020;17(1):150. doi:10.1186/s12966-020-01040-4

- 19. World Health Organization. Noncommunicable diseases. September 16, 2022. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases

- 20. Schwartz J, Rhodes R, Bredin SSD, Oh P, Warburton DER. Effectiveness of approaches to increase physical activity behavior to prevent chronic disease in adults: A brief commentary. J Clin Med. 2019;8(3):295. doi:10.3390/jcm8030295

- 21. Lucini D, Pagani M. Exercise prescription to foster health and well-being. A behavioral approach to transform barriers into opportunities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):968. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18030968

- 22. Rural Health Information Hub. Policy, systems, and environmental change. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/toolkits/health-promotion/2/strategies/policy-systems-environmental

- 23. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. School-based programs to increase physical activity. Published September 26, 2022. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/policy/opaph/hi5/physicalactivity/index.html

- 24. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tobacco free. Smokefree policies improve health. Published September 2, 2022. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/fact_sheets/secondhand_smoke/protection/improve_health/index.htm

- 25. Foh EP, Brown RR, Denzongpa K, Echeverria S. Legacies of environmental injustice on neighborhood violence, poverty and active living in an African American community. Ethn Dis. 2021;31(3):425-432. doi:10.18865/ed.31.3.425 26.

- 27. Virginia Commonwealth University. Center on Society and Health. Mapping life expectancy. Accessed October 20, 2022. https://societyhealth.vcu.edu/work/the-projects/mapping-life-expectancy.html

- 28. United States Department of Transportation. Federal Highway Administration. Complete streets in FHWA. Accessed November 21, 2022. https://highways.dot.gov/complete-streets.

- 29. United States Department of Agriculture. SNAP-Ed Connection. Physical activity. Accessed November 21, 2022. https://snaped.fns.usda.gov/nutrition-education/nutrition-education-materials/physical-activity.