4 Chapter Four: Dietary Interventions for Obesity Prevention

Authored by: Sherri M. Cirignano, MS, RDN, LDN

Chapter Outline

Energy Requirements

Dietary Recommendations

Food Groups

Vegetables

Fruits

Grains

Protein Foods

Dairy

Added Sugars and Fats

Alcoholic Beverages

Dietary Interventions

Energy-Restricted Diets

Carbohydrate-Restricted Diets

Intermittent Diet Strategies

Meal Replacements

Emerging Interventions

Summary

Resources

References

Energy Requirements

To determine the energy requirements needed to achieve a healthy weight, it is necessary to consider an individual’s age, gender, height, weight, and physical activity level, as well as goal weight if appropriate. Although determining energy requirements comes down to a matter of energy in through food eaten and energy out through both biological activities such as breathing and physical activities, it is not as easy as it sounds. There are mathematical formulas and other more precise methods that are used by registered dietitians and other healthcare professionals to determine an individual’s everyday energy needs, but these are not practical for use by the general public. For a consumer to estimate their energy requirements, there are sources such as the Dietary Guidelines for Americans, (DGA) that provide a generalization of estimated needs throughout life.1 This resource includes changes in daily calorie needs based on an individual’s activity level whether it be sedentary, moderately active or active.

In general, energy requirements are higher for males than females, and according to the DGA range from 1,000 to 2,000 calories per day for young children; up to 3,200 calories per day for adolescents; 2,600 to 3,000 calories per day for adult men; 2,000 to 2,400 calories per day for adult women; 2,000 to 2,600 calories per day for older adult men; and 1,600 to 2,000 calories per day for older adult women.1 Keep in mind that calorie needs can be increased during the greatest periods of growth throughout life including during childhood and adolescence as well as during pregnancy and lactation. An increase in calories may also be needed when the body is experiencing stress as a result of major injuries and/or illnesses.

Calculating individual calorie needs is easier than ever with an extensive variety of phone apps and online sources including the MyPlate Plan on the USDA’s MyPlate website.2 How these estimated calorie needs translate to the food we eat is also important to consider. What portion of these calories should come from each food group? The MyPlate Plan can also help with this by linking to an individualized calorie-specific plan including daily recommended amounts to include for each food group. Numerous phone apps, books, websites, and other resources can also be utilized to help determine a specific plan. For example, the Nutrition Facts Label provides calorie as well as other nutritional information on the majority of food packages. Updated in 2016, the changes to the Nutrition Facts Label have worked to achieve a more consumer-friendly look and to provide information that reflects “the link between diet and chronic diseases, such as obesity and heart disease.”3 The goal of the updated label is to make it easier for consumers to make informed food choices.

Dietary Recommendations

Historically, weight management guidelines created to address adult obesity were first offered in the late 1990’s by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute and other guidelines followed in 2003 by the US Preventive Services Task Force, the American College of Physicians in 2005 and the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (formerly the American Dietetic Association) in 2009.4 These guidelines were created to assist healthcare professionals with planning for weight management and obesity treatment.

Further assistance regarding dietary recommendations is available for healthcare professionals and consumers in the DGA. The DGA are published jointly by the US Department of Health and Human Services and the US Department of Agriculture approximately every five years. The DGA are published as a requirement under the 1990 National Nutrition Monitoring and Related Research Act, and they are based on the “preponderance of current scientific and medical knowledge.”5 Utilized to create Federal nutrition education materials by the HHS and USDA, the DGA’s intended purpose is to promote health and prevent disease.

Although some information in the Guidelines have remained fairly constant over the years, the current evidence points each new DGA update in a specific direction. The 2020-2025 DGA were created with a lifespan approach, are the first DGA to provide guidelines for every life stage, from birth through older adults, have a focus on the importance of healthy dietary patterns over individual nutrients and were created with the high prevalence of chronic diseases, including obesity, among Americans in mind.5

The 2020-2025 DGA offer a “customizable framework” that can be adjusted to meet individual needs as well as make choices that are affordable and fit within individual and family traditions and customs. The Guidelines are summarized in the Executive Summary of the 2020-2025 DGA and as follows:

- Follow a healthy dietary pattern at every life stage.

- Customize and enjoy nutrient-dense food and beverage choices to reflect personal preferences, cultural traditions, and budgetary considerations.

- Focus on meeting food group needs with nutrient-dense foods and beverages, and stay within calorie limits.

- Limit food and beverages higher in added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium, and limit alcoholic beverages.

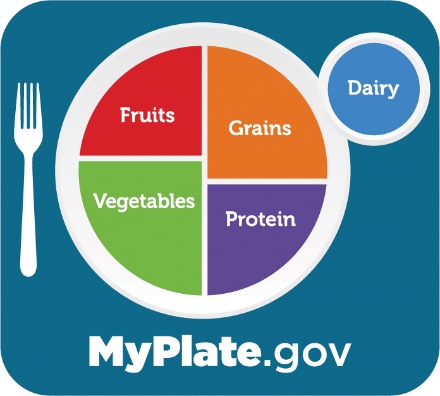

Putting the DGA into practice has been made easier over the past decade since the creation of USDA MyPlate7 (add graphic to pg.) The USDA MyPlate graphic was born out of the 2010 DGA and its use by consumers has been found to be beneficial in determining individual needs through the MyPlate plan6 perhaps due to its simple design. MyPlate is meant to represent a virtual daily plate that includes five food groups-fruits, vegetables, grains, protein, and dairy foods. It’s accompanying resources are updated with each new DGA and can be found on MyPlate.gov. Resources include print materials in both English and Spanish, a mobile app to assist with daily choices, tools to test consumers’ nutrition knowledge and assist with healthy shopping, and MyPlate Kitchen, which includes many healthful recipes and how-to videos.

The current nutrition messages that are provided by MyPlate are as follows:

The benefits of healthy eating add up over time, bite by bite. Small changes matter. Start Simple with MyPlate.

- Make half your plate fruits and vegetables: focus on whole fruits.

- Make half your plate fruits and vegetables: vary your veggies.

- Make half your grains whole grains.

- Vary your protein routine.

- Move to low-fat or fat-free dairy milk or yogurt (or lactose-free dairy or fortified soy versions).

Food Groups

The basis for meeting DGA guidelines and the visuals and recommendations of MyPlate are food groups. From an early age, food groups help us to understand the different food categories from which to choose our daily intake and, with the MyPlate graphic, the recommended amounts to consume from each food group are illustrated. A healthy dietary pattern will include nutrient-dense forms of foods and beverages across all food groups. The 2020-2025 DGA define a nutrient-dense food as follows:

The basis for meeting DGA guidelines and the visuals and recommendations of MyPlate are food groups. From an early age, food groups help us to understand the different food categories from which to choose our daily intake and, with the MyPlate graphic, the recommended amounts to consume from each food group are illustrated. A healthy dietary pattern will include nutrient-dense forms of foods and beverages across all food groups. The 2020-2025 DGA define a nutrient-dense food as follows:

“Nutrient-dense foods and beverages provide vitamins, minerals, and other health-promoting components and have little added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium. Vegetables, fruits, whole grains, seafood, eggs, beans, peas, and lentils, unsalted nuts and seeds, fat-free and low-fat dairy products, and lean meats and poultry—when prepared with no or little added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium— are nutrient-dense foods.”6

Vegetables

The 2020-2025 DGA encourage intake of all forms of vegetables-fresh, frozen, canned, raw and/or cooked-and encourage consuming a variety of colors and types of vegetable including dark green; red and orange; beans, peas and lentils; starchy and other vegetables. Vegetables are nutrient-dense foods, and non-starchy vegetables provide 4 calories per gram of food. Research has indicated that vegetables may have many health benefits including a decreased risk of certain types of cancers, heart disease and obesity.

The 2020-2025 DGA encourage intake of all forms of vegetables-fresh, frozen, canned, raw and/or cooked-and encourage consuming a variety of colors and types of vegetable including dark green; red and orange; beans, peas and lentils; starchy and other vegetables. Vegetables are nutrient-dense foods, and non-starchy vegetables provide 4 calories per gram of food. Research has indicated that vegetables may have many health benefits including a decreased risk of certain types of cancers, heart disease and obesity.

Data on vegetable intake and heart disease risk was reviewed from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from 1999-2014.8 This is a very large ongoing study that assessed the vegetable intake of 38,981 adults during that timeframe. Results showed that those who reported eating dark green vegetables had a lower chance of having cardiovascular disease and coronary heart disease in comparison to those who reported eating no green vegetables.8 A review of studies also indicated that the use of educational interventions to promote vegetable (and fruit) intake significantly reduced weight in overweight and obese individuals.9,10

As a nation, our vegetable intake is not meeting current recommendations. According to the State Indicator Report on Fruits and Vegetables, 2018 released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, surveys indicate that nationally only one in ten adults get enough fruits or vegetables, an average of only 9.3% of adults are eating the recommended amount of vegetables and only 2.0% of high school students meet the vegetable recommendations.11 The report also indicated that those below or close to the poverty level were found to be less likely to meet the vegetable intake recommendations with 11.4% of adults in the highest household income category eating the recommended amount and only 7.0% of those below or close to the poverty level doing so.11

Fruits

The 2020-2025 DGA encourage intake of all forms of fruits-fresh, frozen, canned, and/or dried and 100% fruit juice. Guidelines also encourage consuming at least one-half of fruit consumed as whole fruit, rather than 100% juice. Whole fruits are nutrient-dense foods, providing 4 calories per gram of food.

The 2020-2025 DGA encourage intake of all forms of fruits-fresh, frozen, canned, and/or dried and 100% fruit juice. Guidelines also encourage consuming at least one-half of fruit consumed as whole fruit, rather than 100% juice. Whole fruits are nutrient-dense foods, providing 4 calories per gram of food.

Many studies on the potential health benefits of fruits are conducted in tandem with vegetables. As mentioned above, studies that include both fruits and vegetables indicate their consumption promotes the prevention of heart disease and obesity.9,10 Specific fruits, such as berries, have been the topic of many research studies. Studies on berries have indicated that their consumption specifically provides possible benefits to health including decreasing the risk of certain types of cancer,12,13 heart disease,12-16 obesity, diabetes and in turn metabolic syndrome.16

Approximately only 20% of fruit recommendations are met by the US population, however over 60% of all fruit intake comes from whole forms of fruit, as is recommended.1

Grains

The 2020-2025 DGA recommends focusing on whole grains and limiting intake of refined grains, with the goal of at least one-half of all grains consumed as whole grains. Examples of whole grains include brown rice, popcorn, and whole wheat breads and pastas. The ingredient list is the best way to determine if a food contains whole grains. If it is a whole grain, the grain type would be listed as a whole grain, for example “whole wheat flour”, and would be either first or second in the ingredient list. Many whole grains and whole grain products can be nutrient-dense foods, but not all are considered nutrient-dense. This is dependent on the amount of whole grain in the product, other ingredients present in the product and its preparation method. Grains provide 4 calories per gram of food.

The 2020-2025 DGA recommends focusing on whole grains and limiting intake of refined grains, with the goal of at least one-half of all grains consumed as whole grains. Examples of whole grains include brown rice, popcorn, and whole wheat breads and pastas. The ingredient list is the best way to determine if a food contains whole grains. If it is a whole grain, the grain type would be listed as a whole grain, for example “whole wheat flour”, and would be either first or second in the ingredient list. Many whole grains and whole grain products can be nutrient-dense foods, but not all are considered nutrient-dense. This is dependent on the amount of whole grain in the product, other ingredients present in the product and its preparation method. Grains provide 4 calories per gram of food.

Grains play an important role in the diet by providing essential nutrients including dietary fiber, several B vitamins such as riboflavin, thamin, niacin and folate, and minerals such as iron, magnesium and selenium. Whole grains, when consumed as part of a healthy diet, may also reduce the risk of heart disease, contribute to weight management, and grain products fortified with folate can help to prevent neural tube effects when consumed before and during pregnancy.17

Although meeting overall grain intake recommendations is not an issue for most Americans, 98% do not meet recommendations for intake of whole grains.1

Protein Foods

A healthy dietary pattern with protein foods will include a variety of nutrient-dense foods derived from both animal and plant sources including meats, poultry, eggs, seafood, nuts, seeds, legumes and soy products. Legumes including beans, peas and lentils are part of both the protein and vegetable groups. Protein is also found in foods in other groups including dairy foods. The protein portion of a food from the protein and dairy groups provides 4 calories per gram of food.

A healthy dietary pattern with protein foods will include a variety of nutrient-dense foods derived from both animal and plant sources including meats, poultry, eggs, seafood, nuts, seeds, legumes and soy products. Legumes including beans, peas and lentils are part of both the protein and vegetable groups. Protein is also found in foods in other groups including dairy foods. The protein portion of a food from the protein and dairy groups provides 4 calories per gram of food.

The 2020-2025 DGA recommend protein intake is primarily from lean meats and poultry that are fresh, frozen or canned with avoidance of processed meats. Protein needs can be met for a vegetarian dietary pattern through plant intake, in particular an intake that is higher in soy products; beans, peas and lentils; nuts and seeds; and whole grains.

Protein is important in our diet, providing essential amino acids as well as other nutrients that promote growth, especially in increased times of growth including childhood, adolescence, and pregnancy. However, an excess of protein is not encouraged. A review of studies has indicated that an excess of protein in infancy and early childhood may be associated with an increased risk of obesity in later life.18

Recommendations for intake of protein foods comes close to meeting overall needs in the US population, however, excess intake of protein foods that are high in saturated fat and those that are not in nutrient-dense forms are consumed.1

Dairy

This food group includes milk, yogurt and cheese, of the fat-free or low-fat variety for a healthy dietary pattern, and dairy alternatives including fortified soy products such as soy milk and soy yogurt. These soy products are included in the dairy group because of their similarity to milk and yogurt in use and nutrient composition. Choices from the fat-free or low-fat variety of this food group can be considered a nutrient-dense food. Consuming other plant-based “milks” such as almond, coconut or oat “milks” are not included in the dairy group, thus do not contribute to meeting dairy group recommendations.1

This food group includes milk, yogurt and cheese, of the fat-free or low-fat variety for a healthy dietary pattern, and dairy alternatives including fortified soy products such as soy milk and soy yogurt. These soy products are included in the dairy group because of their similarity to milk and yogurt in use and nutrient composition. Choices from the fat-free or low-fat variety of this food group can be considered a nutrient-dense food. Consuming other plant-based “milks” such as almond, coconut or oat “milks” are not included in the dairy group, thus do not contribute to meeting dairy group recommendations.1

Studies undertaken to determine if there is a link between dairy consumption and obesity in children and adolescents have not been conclusive.19,20 At this time, there is limited evidence to support a need to limit milk and/or yogurt consumption in children and adolescents.

Americans do not meet current dairy recommendations. Approximately only 20% of adults, 34% of adolescents, and 65% of young children drink milk on a daily basis and a majority of dairy consumption is derived from cheese in products such as pizza or in high fat products such as ice cream or flavored, sweetened yogurts.1

Limiting Added Sugars, Fats, Oils and Alcoholic Beverages

Foods with added sugars and/or fats and oils are not included on MyPlate and are often categorized as foods that are calorie-dense and thus provide “empty calories.” Added sugars can be found in a variety of products and include the following top sources and average intakes from the US population starting at age one: 24% from sugar-sweetened beverages, of which 16% is from soft drinks; 19% from desserts and sweet snacks, including 6% from cookies and brownies, 5% from ice cream and frozen dairy desserts and 4% from cakes and pies.1 The updated Nutrition Facts Label now includes the amount of added sugars in food products in addition to the amount of naturally occurring sugars.

Foods with added sugars and/or fats and oils are not included on MyPlate and are often categorized as foods that are calorie-dense and thus provide “empty calories.” Added sugars can be found in a variety of products and include the following top sources and average intakes from the US population starting at age one: 24% from sugar-sweetened beverages, of which 16% is from soft drinks; 19% from desserts and sweet snacks, including 6% from cookies and brownies, 5% from ice cream and frozen dairy desserts and 4% from cakes and pies.1 The updated Nutrition Facts Label now includes the amount of added sugars in food products in addition to the amount of naturally occurring sugars.

Similar to added sugars, foods with added fats and oils, especially saturated fats, add significantly to the American diet. One reason for this is that all fats provide 9 calories per gram of food, more than twice the amount of calories per gram from vegetables, fruits, grains, protein and dairy foods. The top sources and average intakes of saturated fat in the US, ages one and older, are as follows: 19% from sandwiches, of which 4% is burgers and tacos and 3% is burgers and chicken and turkey sandwiches; 11% from desserts and sweet snacks; and 7% from rice, pasta and other grain-based mixed dishes.1

There is significant evidence indicating a link between a high intake of sugar-sweetened beverages and weight gain21 and although weight gain can occur due to the oft high caloric value of foods that have a high fat content, including saturated fats, the direct link between saturated fat and cardiovascular disease have not been supported by recent evidence.22

Alcohol provides a significant amount of energy with 7 calories per gram. Additional calories in mixed drinks can come from the other ingredients, such as juice and soda. As a result, alcoholic beverages can be quite high in calories and thus contribute to weight gain if consumed generously. Light to moderate intakes of alcoholic beverages are not associated with weight gain whereas heavy drinking can be associated with weight gain.23

For those who drink alcohol, the 2020-2025 DGA recommend limiting intake to two drinks or less per day for men and one drink or less per day for women when alcohol is consumed. The following explains what constitutes one alcoholic beverage:

Alcoholic Drink Equivalents1

- 12 fluid ounces of regular beer (5% alcohol)

- 5 fluid ounces of wine (12% alcohol)

- 1.5 fluid ounces of 80 proof distilled spirits (40% alcohol)

For a healthful dietary pattern, a focus on overall diet quality that fits within the food group recommendations found on MyPlate and reviewed above is suggested.

Dietary Interventions for Obesity Management

Energy-Restricted Diets

Treatment for those suffering from severe obesity, also referred to as class 3 obesity, often includes medication and/or surgical interventions. If these treatments are contraindicated or unsuccessful, employing energy-restricted diets have been shown to offer some success.24 Energy-restricted dietary patterns can include low energy diets (LEDs) and very low energy diets. (VLEDs) Defined by The United Nations food standards body Codex Alimentarius, these diets can restrict daily energy intake to between 1000 kcal to 1200 kcal for LEDs and 600 kcal to 800 kcal for VLEDs.24 Total or partial meal replacements are often used in both LEDs and VLEDs and can include shakes, soups and bars as well as other prescribed food items.

A review of studies utilizing LED and VLED dietary patterns have indicated weight loss of 6-16% of initial body weight at one year, with “clinically relevant” weight losses of 10% or more occurring with six weeks or more duration.24 Due to mixed guidelines regarding the use of diets with severe energy restrictions, both in the US and in other countries, and a need for caution due to the nature of implementing energy restrictions, LEDs and VLEDs should be considered for those with severe obesity with caution and should be utilized under the care of a qualified healthcare professional.

Carbohydrate-Restricted Diets

Dietary patterns that restrict carbohydrates (CHO) have also been utilized for obesity weight management. These dietary patterns have employed varying degrees of CHO restriction. According to the National Lipid Association Scientific Statement on this topic, the degree to which CHO is restricted is based on a percentage of the total daily energy (TDE) intake that is coming from CHO. This can range from a moderate-CHO restriction with 26-44% TDE from CHO, to a very-low-CHO diet with less than 10% TDE from CHO. As a reference point, an acceptable CHO range of TDE from CHO for a healthy adult is 45-65%.25

Low- and very-low-CHO diets, including those that are medically supervised, have been used for weight management in obesity for many years. Although the NLA Scientific Statement reports some benefit to the use of these dietary patterns in weight loss, there are safety concerns with their use and overall outcomes have not been found to be superior to other diet methods.25

Intermittent Diet Strategies

In recent years, intermittent fasting (IF) and intermittent energy restriction (IER) have been used for weight management in overweight and obesity as an alternative to energy-restricted diets, where the energy, or calories, are restricted continuously, throughout each day. Because the ability to continuously restrict ones calories is often reported as being difficult to maintain long term, IF and IER have increased in popularity.26 IF and IER refers to when an individual withholds food intake for longer than twelve hours in a day.27 There are a number of IF/IER diet regimens, including when fasting occurs on alternate days, known as ADF (alternate day fasting),26,27 and periodic fasting where fasting occurs two days in a week, also known as the 5:2 diet.26,27 Each IF/IER diet regimen restricts energy intake at certain times and/or on certain days and may include a maximum of 500-600 kcal on a fasting day.27

When compared to continuous energy restricted dietary patterns in systematic reviews and meta-analyses, studies have indicated that although IF/IER regimens are associated with weight loss26,27 and a reduction in waist circumference in some cases,27 they did not show an overall difference in outcomes compared to continuous energy restricted diets.26,27

Meal Replacements

The use of meal replacements is another potentially effective weight management strategy for those with obesity. Defined as “commercially available products fortified with minerals and vitamins”28 that can replace some of or all of meals, meal replacements are beneficial due to their ability to eliminate choice and control intake. Examples of these products include drinks, soups and bars and can also include portion-controlled, ready-to-eat meals.29

Two separate systematic reviews and meta-analyses concluded that the use of meal replacements can be an effective intervention strategy after one year of implementation, particularly when including supportive programming29 and over a standard low-energy diet with ideally 30% to 60% of total daily energy from meal replacements.28

Emerging Interventions

Dietary interventions that focus primarily on some form of energy restriction have had some success in treatment of obesity over many years, especially in the short term, but have had limited success on a long term basis.30 Weight neutral approaches to weight management has more recently been explored as a possible alternative, or addition to, traditional “diets.” Examples of weight-neutral approaches include the practice of mindful eating or intuitive eating. These approaches have been explored in children,31,32 adolescents31-33 and adults34,35 with varying degrees of success. Mindful eating occurs when one is focused on what they are eating and the experience they are having with their food.34 Intuitive eating occurs when one is focused on their hunger and satiety cues as opposed to any diet prescription or calorie restriction.34 Overall, systematic reviews exploring mindful and/or intuitive eating have suggested that these approaches to obesity management could be a beneficial approach to treatment and are in need of more research.30-35 These topics will be explored further in Chapter 11.

Summary

Determining one’s energy requirements and how to meet those requirements is essential in the management of weight, whether for the purpose of maintaining a healthy weight, or for the purpose of losing or gaining weight towards a healthy weight. Although various scientific formulas and other methods are available to precisely determine an individual’s energy requirements, tools are available from a variety of sources including the Dietary Guidelines and MyPlate to quickly and easily estimate needs. Once these requirements are determined, one can then balance what is eaten to meet those needs by considering all of the food groups-vegetables, fruits, grains, protein and dairy-as well as avoidance of added sugars and saturated fats and the limitation of alcohol.

Management of obesity through various dietary patterns have had mixed results over many years. Restriction of both overall energy and carbohydrates have had some positive outcomes, but should be followed with caution and preferably with medical supervision. Newer to the diet scene are intermittent fasting and intermittent energy restriction regimens and diets employing meal replacements. Although intermittent dietary patterns are in need of further study, and initial reviews have not found them to be beneficial over continuous energy-restricted diets, meal replacements have shown some promise. Potentially more promising are the emerging interventions that focus on weight neutral approaches to weight management such as the practices of mindful eating and intuitive eating. At this time, all of these dietary intervention for the purpose of obesity management are in need of continued exploration.

Resources

2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans

Reference

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 9th Edition. 2020. Accessed September 2022. DietaryGuidelines.gov

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. MyPlate Plan. Accessed September 2022. https://www.myplate.gov/myplate-plan

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Changes to the nutrition facts label. Accessed September 2022. https://www.fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition/changes-nutrition-facts-label

- Kazaks and Stern, Nutrition and Obesity: Assessment, Management and Prevention, Jones and Bartlett Learning, LLC, an Ascend Learning Company, 2013.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. 9th Edition. Executive Summary. 2020. Accessed September 2022. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/sites/default/files/2020-12/DGA_2020-2025_ExecutiveSummary_English.pdf

- Schwartz J, Vernarelli, J. Assessing the public’s comprehension of dietary guidelines: use of MyPyramid or MyPlate is associated with healthier diets among US adults. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2019;119(3):482-489.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. MyPlate. Accessed September 2022. https://www.myplate.gov/

- Conrad Z, Raatz S, Jahns L. Greater vegetable variety and amount are associated with lower prevalence of coronary heart disease: NHANES, 1999-2014. Nutrition Journal. 2018;17:67. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-018-0376-4

- Boeing H, Bechtold A, Bub A, Ellinger S, Haller D, Kroke, Leschik-Bonnet E, Muller MJ, Oberritter H, Schulze M, Stehle P, Watzl B. Critical review: vegetables and fruit in the prevention of chronic diseases. Eur J Nutr. 2012;51:637-663.

- Arnotti K, Bamber M. Fruit and vegetable consumption in overweight or obese individuals: a meta-analysis. Western J of Nursing Research. 2020;42(4):306-314.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. State Indicator Report on Fruits and Vegetables, 2018. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2018. Accessed September 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/downloads/fruits-vegetables/2018/2018-fruit-vegetable-report-508.pdf

- Nile SH, Park SW. Edible berries: bioactive components and their effect on human health. Nutrition. 2014;30:134-144.

- Baby B, Antony P, Vijayan R. Antioxidant and anticancer properties of berries. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 2018;58(15):2491-2507.

- Kelly E, Vyas P, Weber JT. Biochemical properties and neuroprotective effects of compounds in carious species of berries. Molecules. 2018;23,26.

- Rodriguez-Mateos A, Heiss C, Borges G, Crozier A. Berry (poly)phenols and cardiovascular health. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62:3842-3851.

- Yang B, Kortesniemi M. Clinical evidence on potential health benefits of berries. Current Opinion in Food Science. 2015;2:36-42.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. MyPlate: grains. Accessed September 2022. https://www.myplate.gov/eat-healthy/grains

- Xu S, Xue Y. Protein intake and obesity in young adolescents: a review. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine. 2016;11:1545-1549. Accessed September 2022. https://www.spandidos-publications.com/etm/11/5/1545

- Dougkas A, Barr S, Reddy S, Summerbell C. A critical review of the role of milk and other dairy products in the development of obesity in children and adolescents. Nutrition Research Reviews. 2019;32(1):106-127.

- Babio N, Becerra-Tomás N, Nishi S, López-González L, Paz-Graniel I, García-Gavilán J, et. al. Total dairy consumption in relation to overweight and obesity in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews. 2022;23(S1):e13400.

- Malik VS, Hu FB. The role of sugar-sweetened beverages in the global epidemics of obesity and chronic diseases. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2022;18:205-218.

- Gershuni VM. Saturated fat: part of a healthy diet. Curr Nutr Rep. 2018;7(3):85-96.

- Traversy G, Chaput JP. Alcohol consumption and obesity: an update. Curr Obes Rep. 2015;4:122-30.

- Maston G, Gibson AA, Kahlaee HR, Franklin J, Manson E, Sainsbury A, Markovic TP. Effectiveness and characterization of severely energy-restricted diets in people with class III obesity: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Behav Sci. 2019;9(12):144.

- Kirkpatrick CF, Bolick JP, Kris-Etherton PM, Kikand G, Aspry KE, Soffer DE, Willard KE, Maki KC. Review of current evidence and clinical recommendations on the effects of low-carbohydrate and very-low-carbohydrate (including ketogenic) diets for the management of body weight and other cardiometabolic risk factors: a scientific statement from the National Lipid Association Nutrition and Lifestyle Task Force. J of Clin Lipid. 2019;13:689-711.

- Schwingshackl L, Zähringer J, Nitschke K, Torbahn G, Lohner S, Kuhn T, et al. Impact of intermittent energy restriction on anthropometric outcomes and intermediate disease markers in patients with overweight and obesity: systematic review and meta-analyses. Critical Reviews in Food Science & Nutrition. 2021;61(8):1293-1304.

- Enriquez Guerrero A, Martin ISM, Vilar EG, Camina Martin MA. Effectiveness of an intermittent fasting diet versus continuous energy restriction on anthropometric measurements, body composition and lipid profile in overweight and obese adults: a meta-analysis. Eur J of Clin Nutr. 2021;75:1024-1039.

- Min J, Kim S-Y, Shin I-S, Park Y-B, Lim Y-W. The effect of meal replacement on weight loss according to calorie-restriction type and proportion of energy intake: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics. 2021;121(8):1551-1564.

- Astbury NM, Piernas C, Hartmann-Boyce J, Lapworth S, Aveyard P, Jebb SA. A systematic review and meta‐analysis of the effectiveness of meal replacements for weight loss. Obesity Reviews. 2019;20:569-587.

- Dugmore JA, Winte CG, Niven HE, Bauer J. Effects of weight-neutral approaches compared with traditional weight-loss approaches on behavioral, physical, and psychological health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrition Reviews 2019:78(1):39–55.

- Brantley C, Knol L, Douglas J. Influence of parental mindful eating practices on child emotional eating: a systematic review of the literature. Cur Devel Nutr. 2022;396.

- Keck-Kester T, Huerta-Saenz L, Spotts R, Duda L, Raja-Khan N. Do mindfulness interventions improve obesity rates in children and adolescents: a review of the evidence. Diabetes, Metabolic Syndrome and Obesity:Targets and Therapy 2021;14:4621-4629.

- Hoare JK, Lister N, Garnett SP, Baur LA, Jebeile H. Weight-neutral interventions in young people with high body mass index: a systematic review. Nutrition & Dietetics. 2022;1-13

- Grider HS, Douglas SM, Raynor HA. The influence of mindful eating and/or intuitive eating approaches on dietary intake: a systematic review. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2021;121(4):709-727.

- Fuentes Artiles R, Staub K, Aldakak L, Eppenberger P, Rühli F, Bender N. Mindful eating and common diet programs lower body weight similarly: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Obesity Reviews. 2019;20:1619-1627.