Part 3: Building a Business

14 Positioning

Finally, a mission statement must address the target market segment: “who will be served by this business?” Researching the mission statements of successful ventures in comparable fields may provide some insight about how this can be done effectively: a statement can be directed at an implied target segment, or the target segment may be indicated more directly.

Art can always be created for the sake of art; as a reflection of society; to advance the boundaries of what is accepted for a certain medium. The business frame of reference need not (and should not) preclude art from being meaningful; rather, if the aim of a certain piece of art is to hold a figurative mirror up to a society, it would be unable to reach its artistic goal unless it was able to connect with people of that society. The relationship between a business and those served by it is central to both the worlds of business and of the arts.

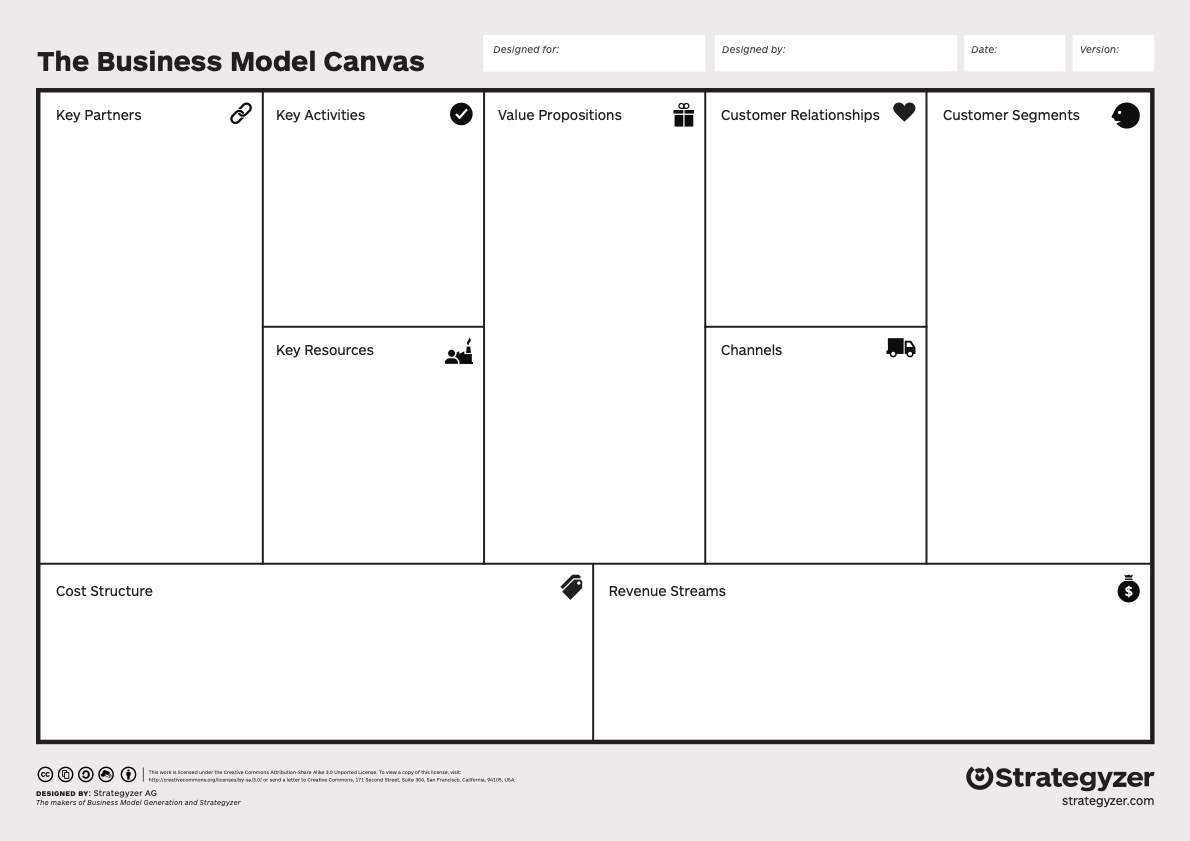

But, in reality, a business will likely interface with a many other businesses and/or consumers. Businesses that aim to bring value to other businesses (sometimes due to scalability or supply chain constrains) could be called business-to-business ventures, or B2B. If a business primarily brings value directly to consumers, it would be a business-to-consumer venture, or B2C. Many companies (even freelance sole proprietors) operate with components that are B2B and other B2C components. To develop a holistic view of how a business operates with and within the world around it, a visual tool like the BMG Canvas (Osterwalder and Pigneur 2010) can help better understand the many interrelated components that make up a company’s business model.

At the center of the canvas are the Value Propositions: what the company makes or does for others; but, surrounding this core region are the means of interfacing with entities which make the value propositions possible (left) and with the segments willing to invest their capital in the value created by the business model (right).

Notably, the Key Partners—entities by whom the creation of the value proposal is facilitated—are treated with as much visual importance as the customers who provide revenue and for whom the business operates. These key partners are interacted with using key activities, and the deliver or provide access to key resources, necessary for development of the core value propositions.

Underlying the relationships between the value propositions and key partners is the cost structure, which, combined with the possible income made from revenue streams that come in through customer segments, determines the financial viability of the model.

In other words, the canvas can be (and has been for many startup businesses) an especially useful tool in helping an entrepreneur think about a holistic picture of how their venture will interact with the world around it. What costs are necessary to run the business? From whom are the expenses incurred, and how stable can that cost structure be over time? How does the venture reach customers, and what key activities should be undertaken to ensure that customers are aware of and make use of the channels through which they have access to the value propositions offered by the business?

Answers to such questions, combined with careful research into the industry in question, form the basis on which a mission statement and eventually a full business plan can be written. These answers should not be treated as static solutions—successful artists and businesses continue to reevaluate their relationships with partners, customers, and competitors in what can broadly be called positioning. As Moore points out in Crossing the Chasm, “positioning” should not be thought of as a passive term, but rather an ongoing, cyclical process through which a company can adapt and thrive in any market.